Frank Lantz recently interviewed me on Donkeyspace, his excellent Substack, which generally focuses on the current AI boom but, in reality, is about his ongoing work on the human condition. As my responses would be of interest to readers here, I’ve reposted the interview below.

Is there a competitive scene for Civ, with tournaments, ranking, etc? If so, do bots have any role in this scene, either as part of the game or for training/analysis?

There is no true competitive scene for Civ although there are a number of small ladders that do the best they can. It’s not really a game that lends itself well to the satisfying resolution needed for competitive play – the closest I ever saw was a grassroots mode where the winner was determined by the first to capture ANY city on the map, which Civ 4 eventually supported as an official mode. However, the lack of a competitive scene means that there is a smorgasbord of different, generally friendly, sub-communities which focus on things like succession games, democracy games, team games, team democracy games, games-of-the-month, challenge games, and so on. Generally speaking, these communities are trying to make a solitary game more social, even if the games played are technically still single-player. A democracy game, for example, is run by a specific player with a group of citizens who vote on important decisions (and sometimes vote out the current player or divide power amongst a cabinet or switch to a new government style or…). The bots are not of much interest here beyond being a consistent measuring stick to use to measure success.

The one exception I can think of is Sullla’s Civ 4 Survivor series (https://sullla.com/civ4survivorindex.html). He’s a long-running 4X blogger, streamer, and critic (provided critical feedback for both Civ 4 and Old World), and he organizes and streams “tournaments” which pit Civ 4 AI leaders against each other to see which ones perform best under different environments and rulesets. He has now added a fantasy version of the tournament where viewers can bid on different leaders before the games begin and then track their success, as one might do in “real” fantasy sports.

I’m curious about all-human, no-AI Civ. Do you know if it’s usually played as a free-for-all or symmetrically (1v1, 2v2, 3v3, etc)? Is it very different from the single-player game vs bots?

Team games and free-for-alls are both popular. Indeed, I’ve spent a good chunk of my career trying to encourage players to forgo free-for-alls for team games as the latter tends to be a much smoother experience (fewer losers, positives emotions from teamwork, less waiting if the game supports simultaneous turns), but there is some instinctive pull that draws players to free-for-alls like moths to a flame. (It’s the same instinct that causes players to always choose the largest map possible and the maximum number of opponents, often to their own detriment.)

Multiplayer is very different compared to the single-player experience, where there is an unspoken, and often unthought, expectation that the AIs will play “fairly” and not suddenly backstab the human (which players will describe as “crazy” AI) or all gang up on the leader as they approach victory. In contrast, humans don’t have any problem – at least conceptually – with other players backstabbing them or ganging up on the leader. It might annoy them, of course, but because they can put themselves in each others’ shoes, they realize they might have done the same thing. Nobody, however, puts themselves into the shoes of an AI. It doesn’t matter if we understand that the AI is just acting like a human might act; AIs are second-class citizens.

When designing games which use AI, it’s important to remember that there are two types of competitive games – games with two sides and games with more than two sides. Two-sided games are inherently zero-sum and thus require no diplomacy at all – all the AI needs to do to evaluate a move is add the move’s value for itself and the negative of the move’s value for its opponent (does this move help me more or hurt my opponent more or some combination of the two). In contrast, games with multiple sides also involve diplomacy, requiring the AI to evaluate who to target, which can involve social and emotional reasoning for which the AI is not extended the benefit of the doubt when it does something the human doesn’t like.

(Of course, many games are actually on a continuum between these two extremes – most free-for-all Eurogames severely limit how players can impact each other so that diplomacy is of little use. Race for the Galaxy, for example, is often accused of being multiplayer solitaire – although the other humans add noise to the system, and mastery comes from predicting that noise. AI works perfectly well for these types of games as the mechanics themselves hinder diplomacy.)

Human-only free-for-all games of Civilization look a lot different from traditional single-player as there is often a lack of trust between humans, which leads to much more defensive play. In single-player, high-performing humans understand how important it is to push out settlers as fast as possible to found new cities; the AI will rarely punish you for doing so as rushing the human is both hard for AI programmers to execute and would also be a bad experience for the players so has been avoided intentionally. In the rare case where the AI does punish the player, the human has an easy emotional out by just reloading or quickly starting a new game, options not available for second-class players (meaning the AI). In multiplayer, players still try to expand quickly but do so in a high-stress environment where they know that an undefended new city could be a game-ending gift to their opponent.

(Old World, by the way, includes a Competitive AI game mode, which is explicitly for players who understand the subtle issues of an AI trying to win against the human at all costs. Under this setting, the AIs will start to dislike you just for winning, will rush a player for expanding too quickly, and will absolutely gang up against the leader near the end. Making this mode an option players have to turn on protects us from most of the standard prejudices that humans bring to a game with theoretically equal AI opponents.)

It seems likely to me that the 1P vs bots version of Civ is the “actual”, canonical version of the game, and the all-human version is a kind of variant. Does that make sense?

It could be considered the canonical version – Civ 1 was single-player after all, and multiplayer was never supported in the initial release until Civ 4 – although that’s mostly a result of the logistical issues with playing a multiplayer game of Civ. A two-team game of Civ is, in my biased opinion, one of the best strategy multiplayer experiences that most people haven’t tried.

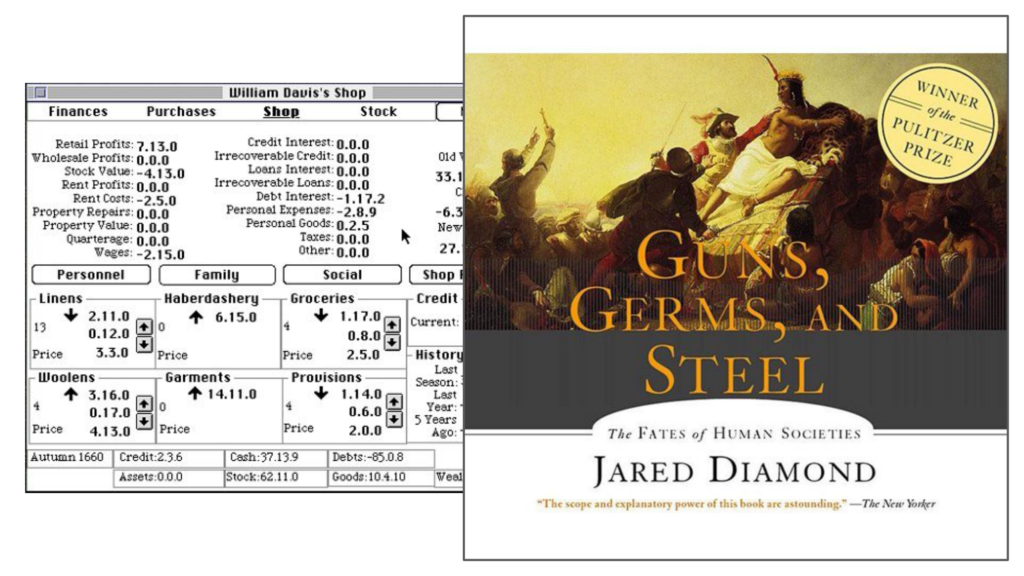

The issue of “infinite city spam” seems to be a constant topic in Civ discussions. This seems like exactly the kind of thing you would need to manage with AI opponents. Was this an issue on the Civs you worked on?

Infinite City Spam has always been an issue for 4X games which allow free settling, and all versions of Civ have tried different limitations to slow it down, from city corruption to exponential maintenance to global happiness to minimum distances between cities. (With Old World, we adopted what has worked for space 4X games since Masters of Orion – fixed city sites.) Allowing the player too much leeway to cram in as many cities as possible onto the map leads to many, many problems, but it’s especially a problem for games which adopt one-unit-per-tile as it reduces the space for maneuvering between cities, turning the map into a permanent traffic jam. The incentive to maximize the number of cities per tiles is another good example of how we intentionally code the AI to play suboptimally by not pushing ICS to an extreme, so taking that option away from the human as well can avoid imbalances between the human and the AI that we don’t want. Further, having well-spaced cities leads to a better general play experience, so there is little reason to sacrifice that just so that one side can get 10% more science or production.

I loved the story about how players learned to exploit the AI’s “land your fleet at the city with the least defenders” rule. I imagine that beating the highest difficulty levels involves finding exploitable weaknesses like this in the AI’s strategy and abusing them, is this true?

These cracks in the AI are probably somewhat akin to finding various speed-running shortcuts in that, after they are discovered, it becomes hard to resist abusing them. (Many of the community-run challenge games will explicitly bar certain types of play that are deemed to be too exploitative.) The AI programmer for Old World, Alex Mantzaris, first got my attention as the player who discovered a code exploit in Civ 3 that minimized corruption as long as you founded your cities in equidistant rings around your capital, which became the dominant way to play until we patched it out (which led to the weird experience that some players missed the fun they had optimizing the equidistant ring puzzle that we had unintentionally created). However, because these strategies often either break the theme or are very unpleasant to execute, we put a high priority on stamping them out in patches so that players don’t optimize the fun out of their games.

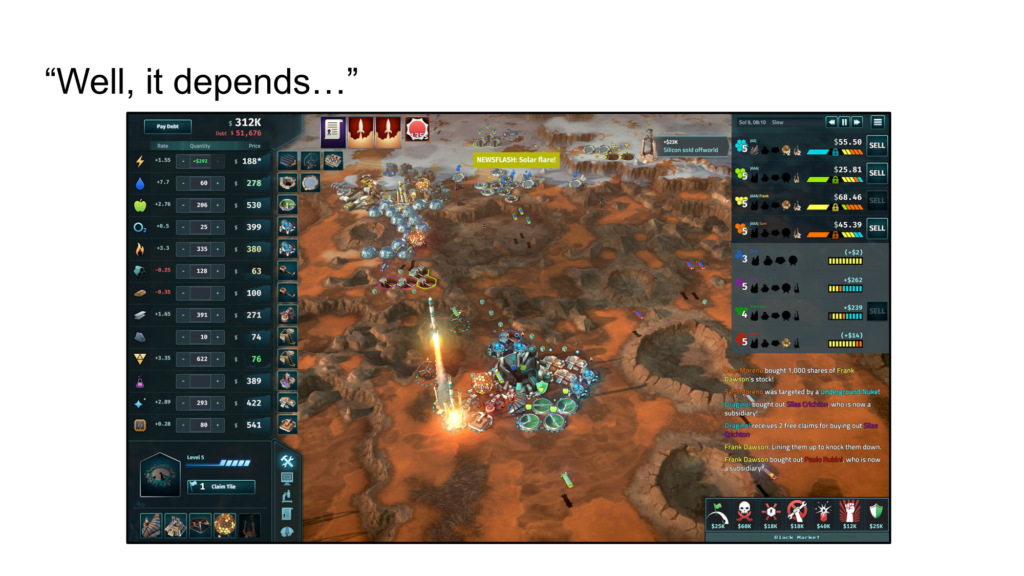

How different are the designs of the AI opponents in Offworld Trading Company and Old World from those you made for Civ?

Offworld was quite different from Civ (and Old World) in that the problems that the AI faced (usually determining which investment had the highest probable rate of return) was something that algorithms usually do better than humans, especially since the game ran in real-time. Further, because black market attacks were both limited and anonymous, the AI didn’t need to grapple with the emotional side of diplomacy as a little Mutiny of a Geotherm was a much smaller decision than a declaration of war. Indeed, Offworld largely feels like a real-time Eurogame where the game has intense competition via mostly indirect conflict. If you don’t have a source of water, and I stop selling my water to drive up the price (or use espionage to trigger an artificial shortage), the effect can be devastating, but it doesn’t feel as mean as conquering the cities you founded and named after your kids. Because of the indirect conflict, Offworld actually works best as a free-for-all; indeed, we were never quite able to make a very compelling team mode for the game.

Old World has many of the same design challenges as Civ – the cursed problem of diplomacy, the human having infinite amount of time to min-max everything, the necessity to give the AI an artificial advantage at higher difficulties – but instead of trying to solve these problems by just writing a better AI, we addressed them at a design level, by making the game explicitly asymmetrical. In reality, all single-player 4X games are asymmetrical (the AI is either not able or not allowed to play the game the same way the human does), but players like to pretend that they are symmetrical. That ostensible symmetry leads to a lot of problems; besides the issues with diplomacy that I’ve covered, there tends to be problems with how games start and end. An AI that begins the game with a single settler is extremely vulnerable to a human rushing it early (which is not a strategy we let the AI pursue). At the end of the game, non-transparent victory conditions (like cultural or religious victory) are extremely unsatisfying ways to lose the game (in which a random popup informs you that you just lost to some other nation you might barely even know).

Thus, in Old World, our AIs start the game AHEAD of the players, as established nations with multiple cities, but are also only able to win the game via victory points, a very transparent measurement of their cities and wonders. Ambition victory, which is managed primarily through the dynamic event system and gives the player ten different ambitions to achieve, is only available to the human, so we never had to make compromises about which ambitions were fair or unfair for the AI to pursue. In fact, the event system doesn’t apply to the AI at all (we simulate the per-turn value of events for the AI as they tend to be positive on average) because we didn’t want to limit what events could do. An event might lead to an unexpected peace deal if, for example, your enemy’s heir shares your personal religion, and she has now taken the throne. These types of events highlight how the AI occupies the role of a second-class citizen; a peace deal like in the previous example is perfectly reasonable for a human to get, but they are not appropriate for the AI. How would the human react if told that they are no longer at war with a weaker nation because its AI got a peace event because their leader is besties with someone in your court. A significant number of players would just shelf the game at that point – their nation is the Middle Kingdom, after all, the center of the universe. There is no room for an AI protagonist in a single-player game.

Players often talk about moves in strategy games in terms of “greed” and “punishment”. Do you think this kind of talk is just metaphorical, or do you think there actually is a kind of moral dimension to these moves?

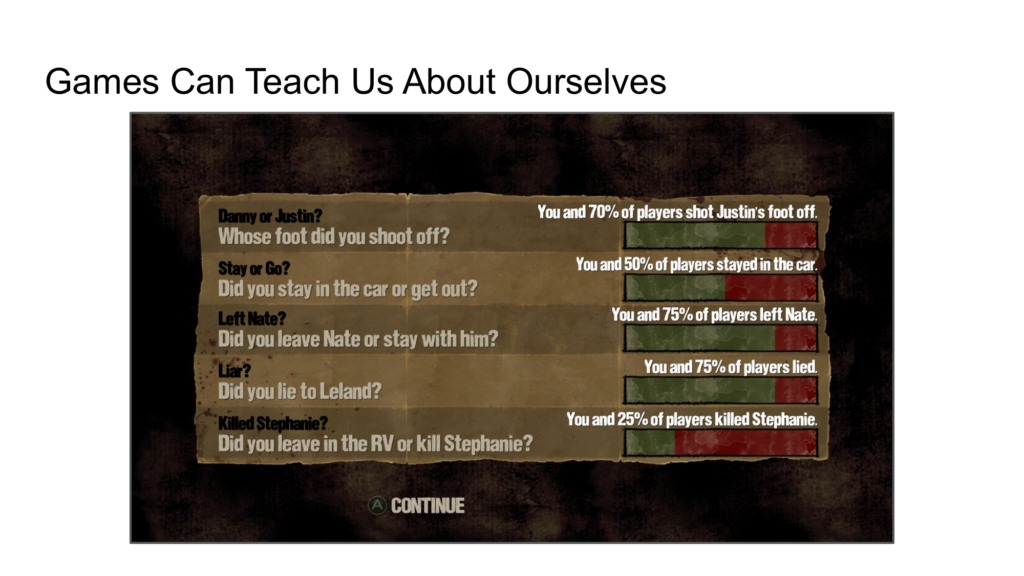

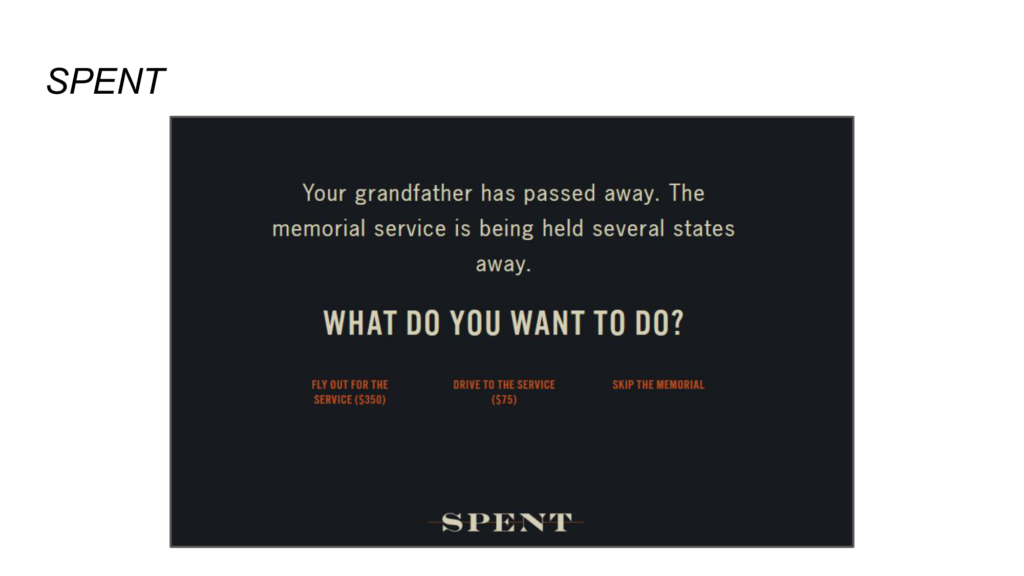

I do think that strategy games can teach us about ourselves, about our strengths and our weaknesses with different types of reasoning. A perfect example is that games can teach us to separate a good decision from a good outcome; I’m sure you appreciate how success at poker requires being able to make that distinction, and it’s hard to imagine an activity that teaches that lesson better than games. I can imagine a parallel universe where Reiner Knizia was born in Republican Rome, and Cato spends his latter years decrying how the youth have stopped playing board games and are now losing their virtue and discipline. There are a bunch of lessons a good game, even an abstract game, maybe especially an abstract game, can teach: the sunk-cost fallacy, the endowment principle, understanding probability, long-term vs. short-term decisions, avoiding tilt, and so on.

We recently played a bunch of the board game Pax Pamir together, a game neither of us had played before, and you were much better than me. Do you have something like an algorithm that you could write down that captures how you think when you encounter a new game and are deciding which moves to make, or are you just intuitively winging it?

Relative to the average gamer, I tend to do pretty well the first few times through a game (and then fall back to the pack), and it usually comes down to figuring out the most likely mechanic that will deliver victory. With Pax Pamir, I felt it was unlikely that any of the three coalitions would gain dominance in our first few games, so victory would come down to whoever got the most of their own pieces on the board, so I placed as many spies and gifts as I could as that seemed the cheapest way to be in the lead. (Tribes, on the other hand, make you a tempting target.) I also realized that the game was NOT actually an engine-builder even though it gave the outward appearance of being one. The strict tableau limit, the fact that placing cards competes with using cards for actions, and the opportunity for your rivals to kill your cards means that one needs to think of cards as temporary, with their placement bonus being more important than their ongoing capabilities. I think many new players assume the game is an engine-builder because it looks like one, but engine-builders require permanence – the whole point of playing a long-term card early is knowing that it will pay off later. When Tom Lehmann designed Race for the Galaxy, he gave himself an early constraint that no card could damage another player’s tableau, as it would lead to a completely different experience at odds with being an ideal engine-builder. Pax Pamir is perhaps that alternate version of Race – Pamir is not a bad engine-building game, it’s a good some-other-sort-of game.

Do you think that it would be possible to make a game-playing AI that played “for fun” the way we do? That was interested and curious, that learned the game over time, that could get bored, angry, distracted, addicted, proud, etc? If so, would that be a third category, beyond the “fun” AIs that are really just opponent-themed game rules and “good” AIs that are attempting to play optimally? Can you think of any games that have done anything like that?

This question raises another question that I wonder about – is there any point interviewing me about machine learning “AI” just because I work on game “AI” as the two fields are so fundamentally different? The big difference is that, to some extent, most ML AI involves some sort of black box, and we’ve discovered that if you try a lot of black boxes and cram an enormous amount of data into them, you’ll eventually get great results. However, one is never really sure WHY the AI is making the choices it does, which means that it can be a useful tool for a game where the rules have zero chance of changing (in other words, go and chess) and where performance can be reasonably evaluated objectively (we only care if the go or chess AI wins, not if the human has a good experience). Both of these vectors are at odds with actual game design work, where iteration is a given and, generally speaking, we want the AI to grasp defeat from the jaws of victory.

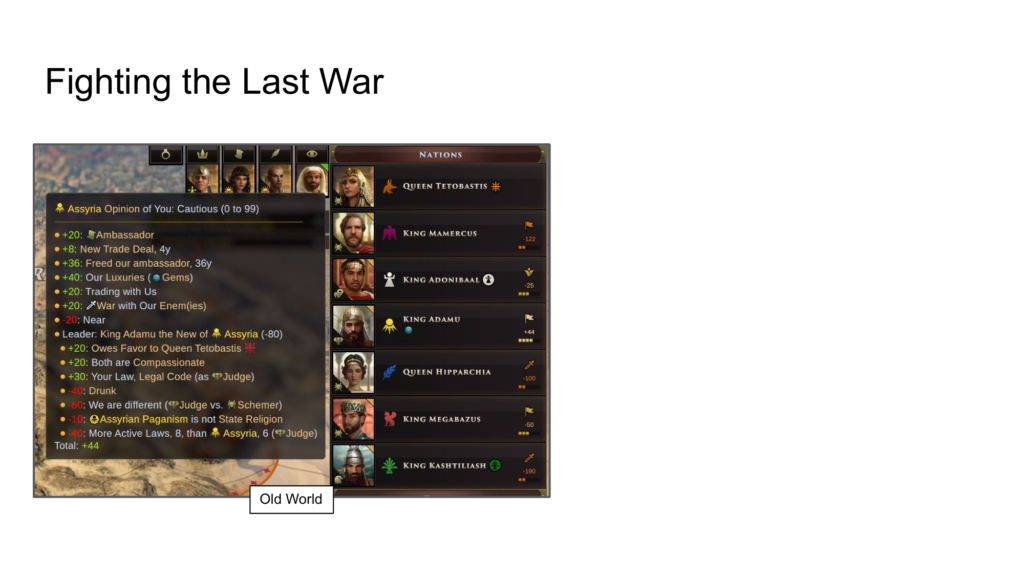

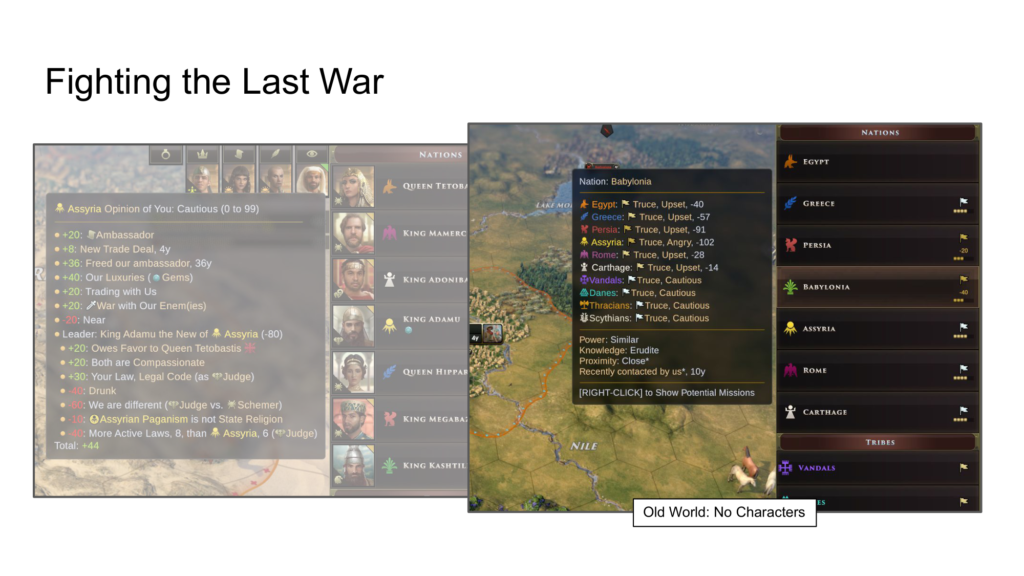

Also, before answering the question of an AI playing “for fun”, I am contractually obligated to reference the other line that Sid is well-known for – to paraphrase, we should always ask ourselves who is having the fun, the player or the computer? Further, it doesn’t matter how much internal emotional depth the AI has if that is not made transparent to the player, who will probably just interpret the AI’s mood swings as random chance, or worse. (If we postulate a future world where humans extend the same theory-of-mind to AIs that we extend to one another, perhaps the answer will be different, but I also suspect that if players really wanted this kind of depth in their opponents, then single-player game modes would be a lot less popular.) Thus, I am largely skeptical that a “genuine” emotional AI would make an ideal opponent. In contrast, “fake” emotional AIs (no magical machine learning, just old-fashioned integer math) are quite useful. Since Civ 3, I’ve had AI opponents describe their attitude towards you using a simple enum, from “friendly” to “cautious” to “furious” – levels which have concrete effects on how the AIs play and also transparent inputs that make intuitive sense.

A lot of people are worried about AI destroying civilization (the actual one, not the game.) Are you worried about that? Does your experience designing AIs for games influence how you think about this issue?

I have a hard-to-suppress instinct that if James Cameron hadn’t made a movie about AI-controlled robots attempting to destroy humanity, we wouldn’t be having this discussion. No matter how generous our reading of ChatGPT or other models are, even if we are willing to extend the label of intelligence to them, they don’t have any agency, let alone any needs, memories, or goals. If we don’t prompt them to write our term papers for us, they don’t do anything on their own. So, it’s really a question of what we let AIs control because, similar to the problem with using machine learning for games, the main issue is that these AIs are inherently unpredictable. So, let’s not give AIs autonomous control of heavy weaponry, alright?