I gave a short talk at GDC this year on the importance of understanding what your game has inherited from the past. They have already posted the video here (my part starts at 28:50):

Since my talk was short and scripted, I am also posting the slides and words for your reading pleasure!

This phrase is so common, it’s basically an idiom. Indeed, while some of our non-American friends here might be baffled by baseball in general, they probably still know this rule. However…

…it’s not actually true. The batter is not out after the third strike. It’s only when the catcher catches the ball that the batter is out.

If the catcher drops or misses the pitch, then the batter is not out and has a chance to advance to first. This almost always results in an out as the catcher simply picks up the ball and makes the easy throw, but occasionally, this little-known rule can become a big deal, as it did in last year’s final game in the playoff series between the Chicago Cubs and the Washington Nationals. Max Scherzer threw a third strike past a swinging Javier Baez, but watch what happens…

…the Nationals catcher Matt Wieters missed the ball between his legs, allowing Baez to make it safely to first base. This would have been the third out of the inning. Instead, the Cubs scored two more runs and later won the game by only one run and advanced to the next round.

Thus, an obscure rule knocked the Nationals out of the playoffs. Where exactly did this rule come from?

It actually reaches back to the very first time the rules of baseball were put down in print, by the German Johann Christoph Friedrich Gutsmuths.

He outlined something called “English Base-ball”, which was a game of innings with a batter, fielders, safe bases, and scoring at home plate. However, there were no strikes or balls yet. The pitcher stood close to the batter and more or less “delivered” the ball as a soft lob to be hit. The pitcher wasn’t trying to challenge the batter; the game was about fielding the ball AFTER it was hit.

However, what happens when there is a terrible batter who can’t hit anything? In Gutsmuths’ game, he had a special rule for this situation – the batter gets only three swings. On the third swing, the ball is automatically in play whether it is hit or not. So, the batter will run to first either after hitting the ball or missing for the third time. Indeed, there is no catcher to receive the ball; so the pitcher would need to run to home plate to pick it up and throw to first.

In 1845, the American Knickerbocker Base Ball Club wrote down their rules for the game, and some things had changed.

The pitcher was now much farther from the batter and threw the ball horizontally, which required the new position of catcher. However, they preserved the logic of the old Gutsmuths rule – that the ball was in play after the third missed swing – like old legacy code lying around.

The “strikeout” was actually emergent gameplay because after the third miss, the ball was now technically in play, and the catcher turned it into an out by catching the pitch. Thus, there was no actual difference between the catcher making an out from catching a popup and the catcher making an out from catching the pitch after a third missed swing. In each case, the ball was now “live” and the catcher made an out by catching the ball before it hit the ground.

However, they had to patch the game later because of an unintended consequence of not taking the time to make the strikeout an official rule. Because the ball would be considered “live” after a third strike, the possibility for a cheesy double- or triple-play existed.

For example, if the bases were loaded, then the catcher could intentionally drop the ball, pick up it up again, step on home plate for an easy out, and then throw to third and on to second for two more. Therefore, in 1887, they added a new rule so that the batter would automatically be out if a runner was on first base AND there were less than two outs.

Thus, Three Strikes and You’re Out – the way everyone assumes baseball is played – is true… but only under a very specific set of circumstances. They opted for an ugly patch instead of just rewriting the rules to match how the game was actually being played!

Indeed, think about the situation with Javier Baez. There WAS a runner on first base… so, even though the catcher dropped the ball, it should have been a strikeout… except, there were two outs, so we’re now back to the original dropped third-strike rule again.

They could have just rewritten the rules so that Three Strikes and You’re Out applies at ALL times. Wouldn’t that be simpler? More intuitive? Why go to the trouble of fixing the one glaring issue with catchers intentionally dropping the ball and not just get rid of the old, vestigial rule.

The reason is that we inherit our game design from everything that comes before us.

Sometimes, this inheritance is obvious – Civ 6 inherited from Civ 5 which inherited from Civ 4, and so on.

Sometimes, a designer inherits from the games he or she played as a kid (Mario -> Braid, Myst -> The Witness)

Sometimes, games inherit from themselves. This is a timeline of the development of our economic RTS Offworld Trading Company.

You might make certain development shortcuts or hacks early on just so that you can get your prototype playable, but then these assumptions are now baked into your design whether you want them there or not. You have to REMEMBER that it was an accidental or arbitrary choice.

The most common thing to inherit, however, is game mechanics, usually from games in the same genre.

For example, although Offworld Trading Company is an RTS, it’s notable for being one without units. However, we didn’t start there as we inherited from all the other RTSs before us – StarCraft, Age of Empires, etc. Thus, we had scouts, builders, transports, pirates ships, police ships, and so on.

Over time, we discovered that this inheritance was weighing the game down, forcing the player to spend time wrangling units that would have been better spent playing the market. Slowly, we took these units out one by one, first the transports, then the combat units, then the builders, and finally the scouts. The game looks like a radical break with the past, but it took us a long time to get there.

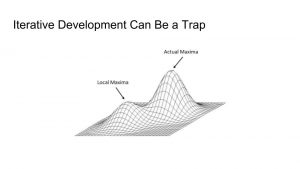

The problem is that iterative design can be a trap – that you can no longer see those parts of your game that are holding you back from a much better design. It’s easier to make small changes that fix glaring issues rather than to re-evaluate your entire design

Sometimes, the problem with a game’s inheritance can be at the conceptual level. Consider Spore…

…which was conceived of as a “Power of 10” game that went from cellular-scale all the way up to galactic-scale. That was the hook, the point of making the game.

This part of the game was widely seen as a disappointment – that the five disparate levels felt like five different games duct-taped together. However, something interesting happened with the failure of Spore…

…which is that it wasn’t actually a failure after all. This is how many people are playing Spore right now – not bad for a 10-year-old game.

Indeed, check out this chart, which compares Spore to the two most successful PC games released the same year – 2008. Spore currently crushes them, and keep in mind that Spore didn’t even launch on Steam.

What happened was that the most interesting part of the game did not come from the Powers of Ten concept, but from the editors inside the game – especially the creature creator, which dynamically animated the players’ creations.

However, these editors were developed midway through the project; Maxis started making a game about one thing and accidentally ended up making a game about something else. One of the big unanswered questions about Spore is what could we have done if we had been able to ditch the Powers of Ten concept and refocus the game on the editors?

Here’s a classic case study in inheriting bad design. Creep denial is a mechanic in the original DOTA where you kill you OWN units to keep your opponents from getting gold and experience from them.

Indeed, creep denial is one of the focal point of high-level play in DOTA, to maximize your experience point gain relative to your opponents to outlevel them. However, it’s an open question whether this is actually GOOD design.

At the very least, creep denial is ACCIDENTAL design because DOTA inherited it from Warcraft 3 – this was simply how that game handled killing your own units. Indeed the fact that Warcraft 3 even ALLOWED killing your own units was likely an afterthought by the designers.

DOTA inherited this rule because the game was literally built inside of Warcraft 3 as a mod. Thus, MOBAs inherited a ton of design and mechanics from Warcraft 3. The original DOTA designers may have wanted many things to work differently, but they really didn’t have a choice given the limitations and assumptions of the Warcraft 3 editor.

DOTA 2 and League of Legends, of course, inherit their design from the original DOTA mod, but they made different choices about their inheritance of creep denial. Basically, League dropped it while DOTA 2 kept it.

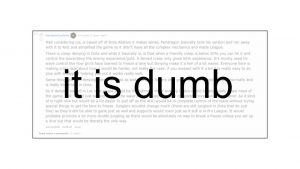

This is from a Reddit thread on why creep denial is not in League. Don’t worry about reading this; I just want to point out how “RandomGuyDota” is trying to explain why creep denial is bad for the design using the game mechanics themselves. This is pretty typical reasoning for something that has become part of a game’s design inheritance – the burden of proof is always on why it should be removed from the game, not on how it got added in the first place.

However, I have a simpler explanation for why creep denial is bad design…

I mean, come on, you want your players to be spending their time killing their own units? Is that really a core part of what makes MOBAs work? The game would fall apart if you couldn’t kill your own guys?

aahdin perhaps sums it up better than I ever could.

At some point, you have to step back as a designer and re-evaluate your inheritance. Does the core gameplay survive without the feature? Is the feature unintuitive, making the game harder to understand or to pick up? Is there a better way for the players to be spending their time than on this feature?

In the case of creep denial, the answer to all those questions suggests that the game would be better off without it. There is only one magical core feature to MOBAs, the one feature which cannot be dropped – and that is taking the scope and complexity of an RTS but focusing the player’s control onto just one unit, which makes the game accessible to a larger audience by an order of magnitude. Everything else, EVERYTHING ELSE, is just accidental inheritance resulting from the genre’s origin as a Warcraft 3 mod.

In fact, although League doesn’t have creep denial now… they actually started with it.

These are League of Legend’s very first patch notes, published in July 2009. They inherited creep denial but killed it very early. So, although they got it from the original mod, they were willing to critically examine their game’s past.

In contrast, here is the history of creep denial from DOTA 1 to DOTA 2. You can see an awareness that creep denial might not be the best thing for the game.

Look at 6.82 – “Denied creeps now give less experience” – a clear sign that they are re-evaluating this feature by changing its rewards. However, instead of ripping it out, they are making small changes around the edges.

Basically, they are doing what baseball did when they patched the dropped third-strike rule by making it not apply in certain circumstances instead of just getting rid of the dumb rule itself.

Remember my questions on the value of creep denial? Does the core gameplay survive without the feature? Is the feature unintuitive, making the game harder to understand or to pick up? Is there a better way for the players to be spending their time than on this feature? Running this exercise with the dropped third-strike rule gets us to the same place – that it’s bad, accidental design that is ultimately hurting baseball.

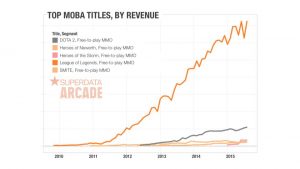

Now, here’s a comparison of the two games, and some other MOBAs. There are many reasons why League outpaces DOTA 2 by an order of magnitude – an almost three year head start is a pretty big one – but I also believe that Riot’s philosophy of re-examining their inheritance from the original DOTA mod, which extends well beyond just removing creep denial, is a very important piece.

Now, I also have thoughts about last hitting, but fortunately, I don’t have time for that. I say fortunately because, Heroes of the Storm, which is the only one of these three to drop last hitting, is less successful than DOTA 2, let alone League. Thus, I can’t really make an argument that the market has proven that last hitting is bad design. Further, I don’t think it would be reasonable to expect Riot to experiment with dropping last hitting at this point; it’s just too late. League is one of the world’s most popular games. Indeed, they are lucky that they dropped creep denial so early in their development before doing so might have split community opinion.

We don’t always have the luxury of looking at the market to prove out our decisions, which is why re-examining a game’s inheritance is such a difficult and important issue.

Choosing to erase your inheritance takes real bravery. Sometimes, you have to trust your own rational design process if you see a problem. Sometimes, you have to go with your gut. Ultimately, you must be willing to see your history, know how it led you to where you are today, and then have the courage to drop the past.

(For more background on the dropped third-strike rule, check out this article.)