I gave a talk on games and meaning at GDC 2023, which is now available on YouTube:

However, I fully scripted the talk ahead of time, so I decided it would be worth taking the time to post the slides online, in three parts to have mercy on your browser.

Besides the question of whether we know what we are doing as designers, what about the question of whether games can teach us anything about our world.

Or, maybe, let’s set the bar lower and see if games can at least teach us anything about sports.

To do that, we need to talk about baseball analyst Voros McCracken.

Who, despite his preposterous name, has no relation to either Zak McCracken or the Alien Mindbenders

Instead, Voros McCracken revolutionized our understanding of baseball with an idea he first published on Usenet in 1999. He called it DIPS, which stands for Defense Independent Pitching Stats.

The basic idea is that while pitchers do have control over balls and strikes, once the batter hits the ball, the results are no longer in their control. In other words, barring a strikeout or a walk, pitchers don’t control how many hits they allow.

This may seem like a fairly simple observation, but baseball is a very old game, and for over a century, everyone had assumed that the opposite was true – that some pitchers were better at getting batters out than others.

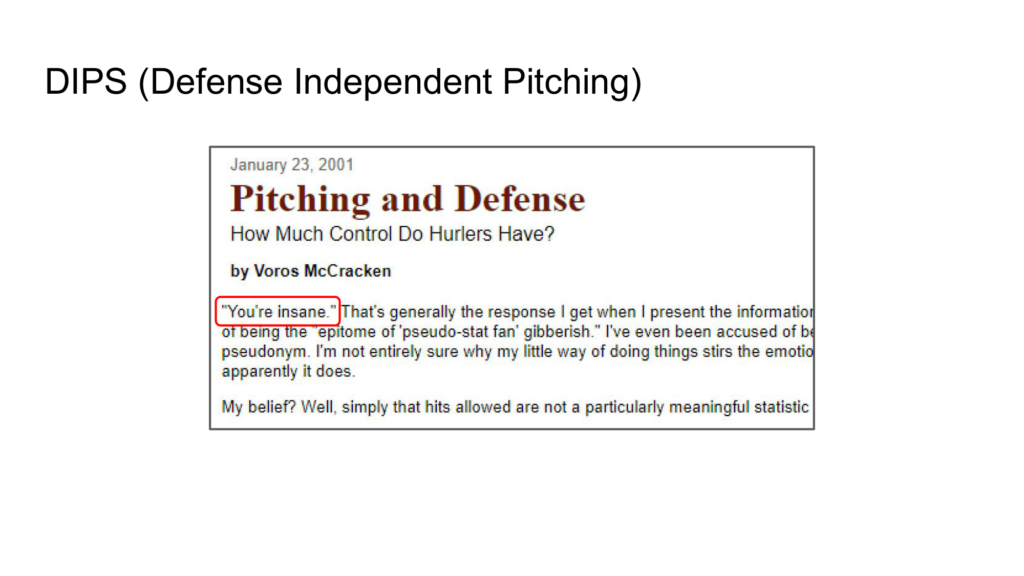

The initial response to McCracken’s idea, which threatened to turn our understanding of pitching upside-down, was shock, disbelief, even hostility.

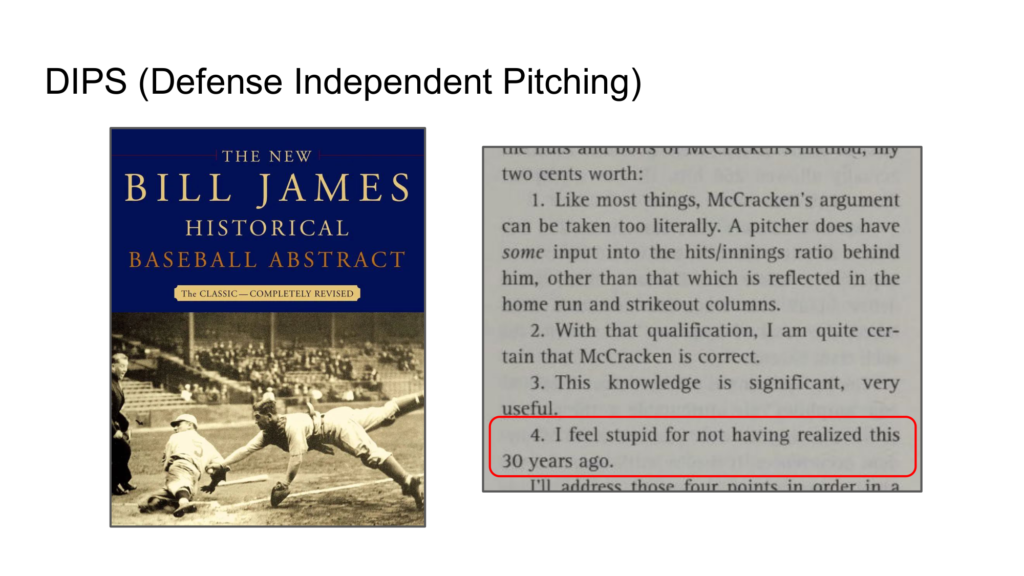

Although Bill James, the patron saint of progressive baseball analysis, was initially skeptical, after doing the research, he determined that McCracken was correct and that he felt “stupid for not having realized this 30 years ago.”

So, why am I talking about DIPS? What does this mean for video games? Well, one part of the appeal of games is that they can theoretically simulate the real world and teach us about it, that we can make choices and see those choices be modelled accurately. But, to use just this one specific example, how could a game written before McCracken’s insight on pitching have any claim to accurately model baseball? The programmers writing these games would absolutely make some pitchers better than others at preventing hits because that was how everyone thought baseball worked before McCracken. And of course, if garbage goes in, garbage comes out. These games could only simulate a faulty understanding of how baseball works.

To underline this point even more, consider this article Bill James wrote in 2015, arguing that baseball managers were using their starting pitchers incorrectly. For decades, teams have used a five-man rotation, meaning that there is a new starting pitcher every fifth day so that each one can pitch at full strength after four days of rest. James argues that teams should instead use a three-man rotation but with much lower pitch counts, relying more on relief pitchers.

Let’s say someone wanted to test this theory with a baseball simulation. Well, even with a sport like baseball that is ideally suited for simulation as it is essentially a turn-based game, there is no way to get good results on a three-man rotation because baseball simulations are written by trying to get their internal numbers to match real-world results, not from some deeper understanding of how baseball actually works which would then produce accurate results. Because no one has tried a three-man rotation in real life, no one knows what would actually happen, how a pitcher would hold up to pitching every three days instead of every five. Game designers would just be guessing.

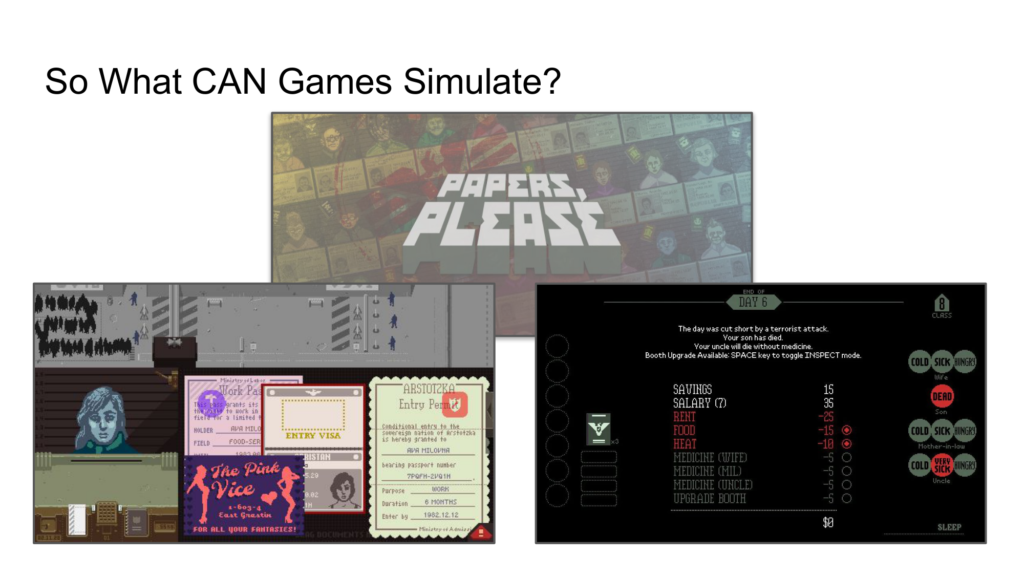

So, what can games simulate? Strangely, the best example I can think of is a game trying to recreate a situation MUCH more difficult to simulate than baseball, life as a border agent in a totalitarian country. Papers Please succeeds because instead of trying to simulate reality, it is trying to simulate the personal tensions someone in this position might feel.

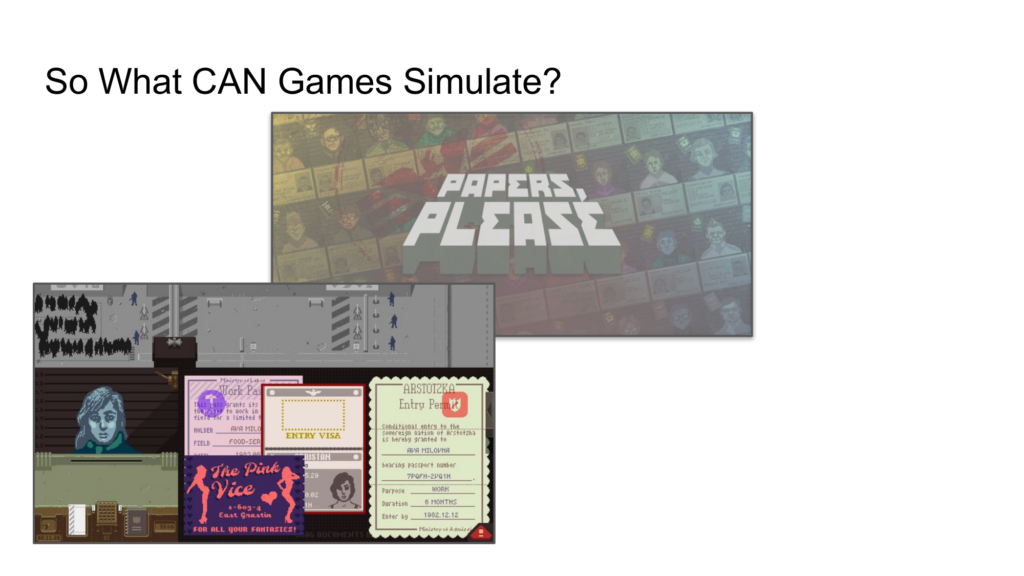

The game puts you in difficult situations as a border agent processing immigrants who have compelling stories for why they are trying to cross the border. Would you stop a young girl fleeing from abuse just because she doesn’t have all her papers in order? Who will you let in and who will you keep out? What laws will you enforce and what will you turn a blind eye towards?

However, letting people in illegally can lead to citations which carry fines that might lead to your son dying because you don’t have enough medicine.

Is this an accurate simulation? I mean, who knows? But it creates a genuine emotional conflict which we can all relate to – Is there a right thing to do when helping someone in need will hurt your family? Losing your family is a loss condition, so you can’t just perform as a paragon.

Through this tension, Papers Please gives players an understanding of why resistance against an oppressive system is so hard for people with real lives and, thus, why the powerful are able to stay in power.

So, to put it simply, games can simulate empathy much better than they can simulate reality.

Speaking of which, here’s a classic line on one of game’s most famous simulations: SimCity doesn’t actually simulate a real city. It simulates the inside of Will Wright’s brain.

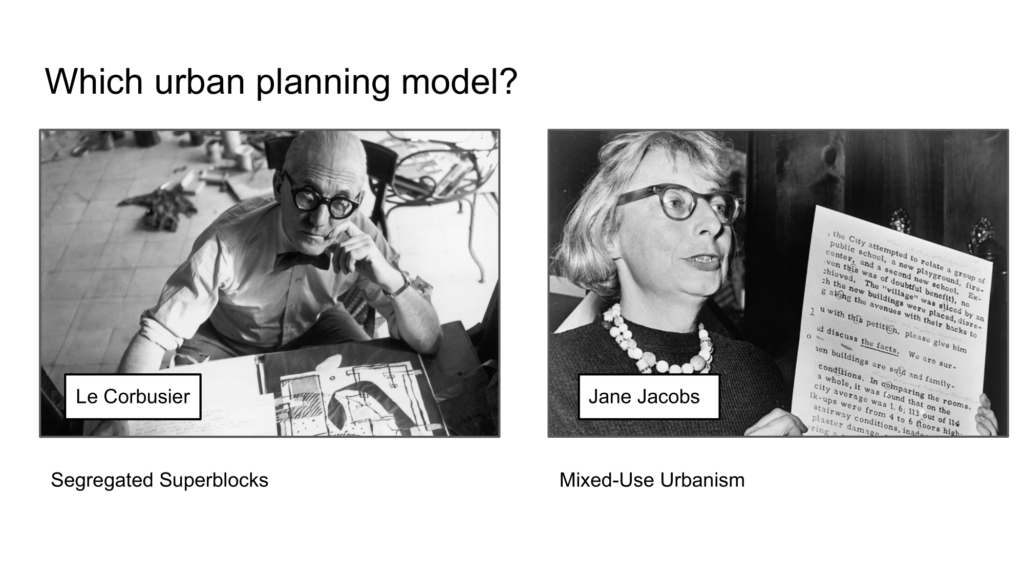

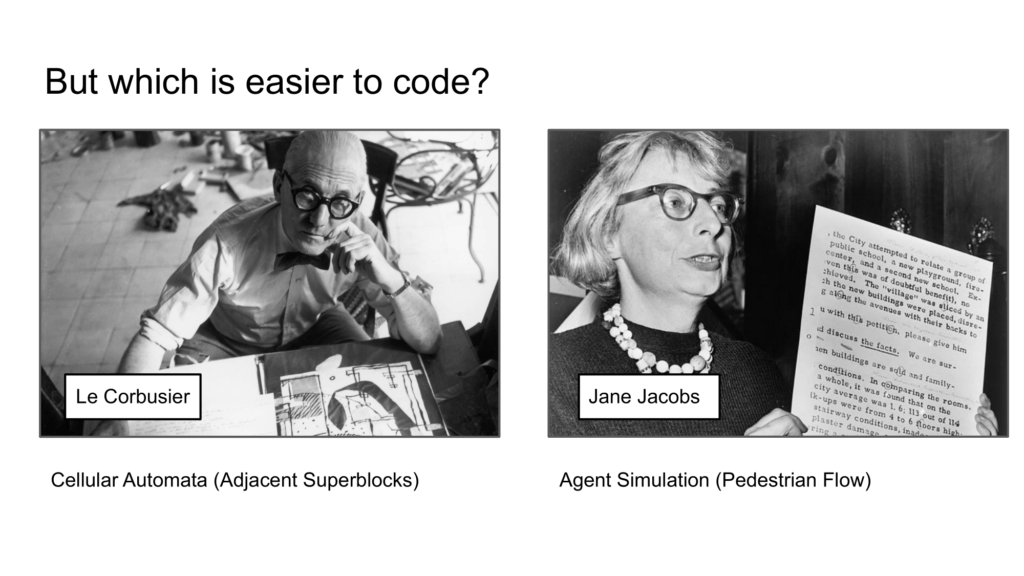

Except that’s not exactly true. Very crudely, here are the two poles of 20th-century urban planning. Le Corbusier, who was a proponent of top-down, rational city planning, which separated residential, commercial, and industrial areas. In contrast, Jane Jacobs challenged this idea with proposals for mixed-use development which reflected how cities traditionally grew without central planning.

When Will Wright talks about urban planning, he is much more likely to praise Jacobs than Corbusier. Her more contemporary ideas are the ones he would commonly refer to in his sprawling game design talks.

For example, in this interview, when asked about the inspirations for SimCity, the one urban planner he mentions is Jane Jacobs, not Corbusier.

However, Wright was not making a game in the abstract. He was trying to create a whole city on a very real Commodore 64, and the ideas of these two designers required very different types of coding. Jacobs’s mixed-use urbanism, which focused on pedestrian flow, would require agent simulation, which would be much too complex for an 8-bit system. On the other hand, Corbusier’s residential, commercial, and industrial superblocks could be handled by much simpler cellular automata, which is what Wright choose to use. In other words, the limits of the technology determined what type of city SimCity would simulate, regardless of what Will Wright might have actually believed.

So, SimCity ended up with the famous residential/commercial/industrial split that a rationalist planner like Corbusier might admire, and which – it needs to be said – is today considered bad urban design that leads to crime, slums, and general economic and social decline. As an admirer of Jacobs, Wright probably understood this too – so that leaves us with the question, what meaning should we take from the first SimCity if it represents an urban model that the designer himself doesn’t even believe in?

Is this intentional design? Accidental design? Something else?

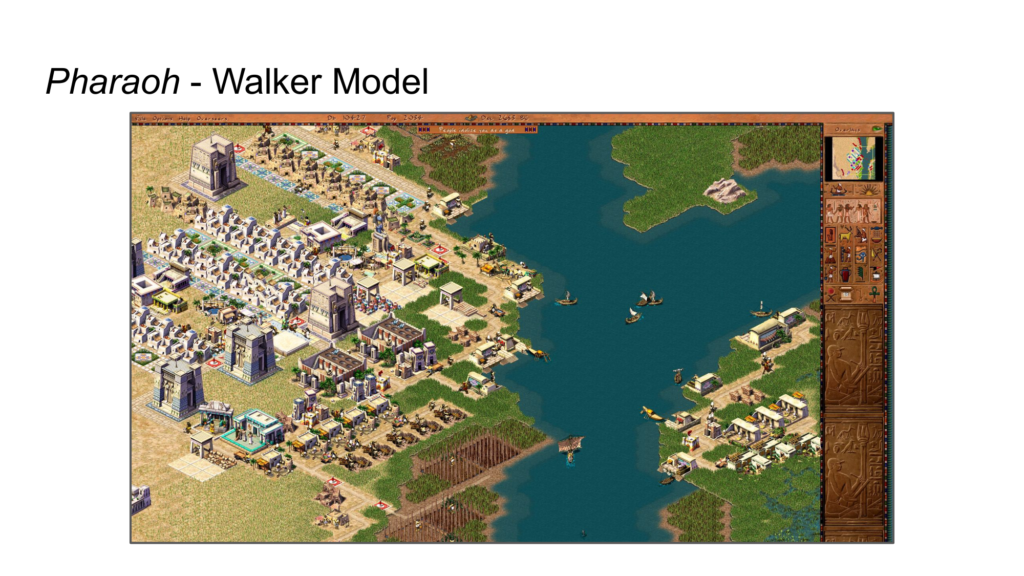

There is actually a successful city builder based on the type of agent simulation needed to support Jacob’s ideas. Pharaoh doesn’t use districts; instead, its systems are built around little walkers that move around your city and do their jobs, so that the layout of your streets and the adjacency of your buildings actually matters. The game is considered a high-water mark for city builders, and a testament to how choosing the right model can matter.

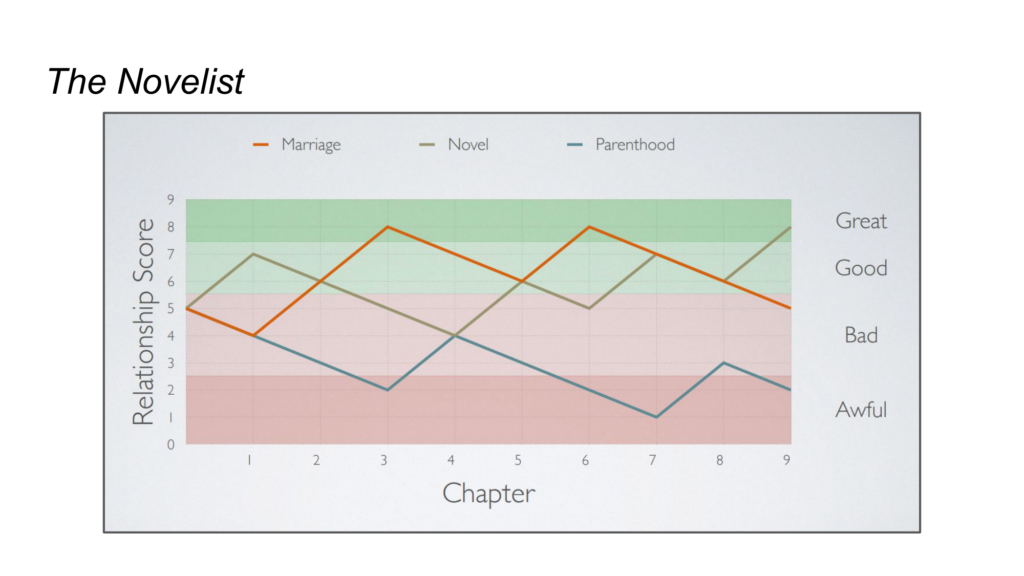

I’d like to talk about another game, Kent Hudson’s narrative simulation, The Novelist, which explores the story of the title character who has troubling balancing his three biggest priorities – his wife, his work, and his son.

The game presents you with choices over the course of nine chapters, moving you up or down in those three different categories. The inner math is zero-sum so if you gain two points in your marriage, you lose two points between your work and your son.

However, after playtesting, Hudson realized that his game’s meaning was the exact opposite from what he wanted:

My game was telling players: You can’t have it all. Life is zero sum. You can’t win.

I don’t believe that statement to be true, but people were taking a message from the game that I fundamentally disagreed with.

Games can escape the intentions of their designers just so easily.

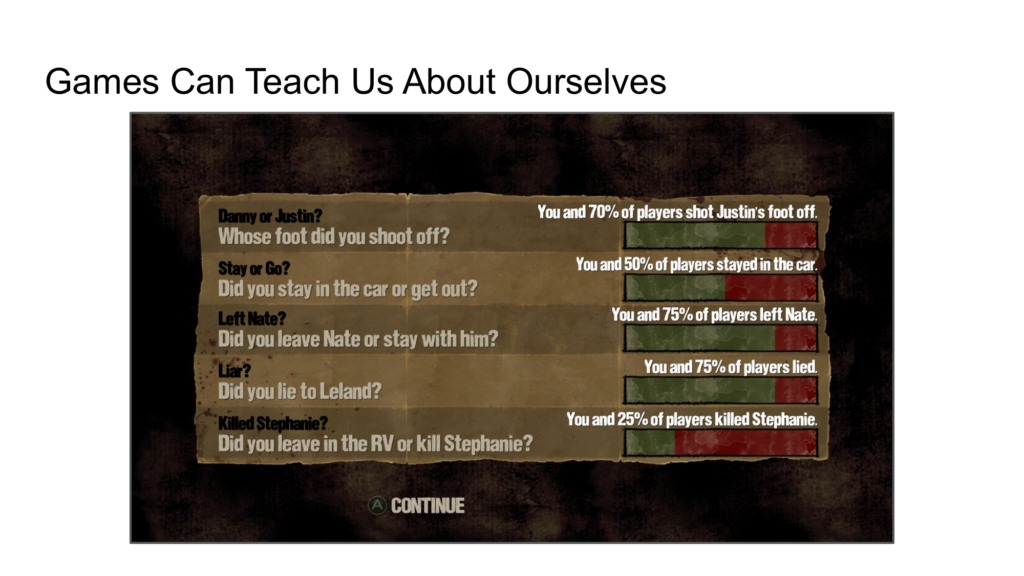

I think one of the issues games like The Novelist face is that it’s hard to find human meaning in a game with just simple math at its core. Yet, games absolutely can teach us about ourselves. Telltale’s Walking Dead games provide a great example of this by showing you how your choices compare to everyone else’s. If you are one of the 25% of players who killed Stephanie, you might reflect on why you made that choice when so many others didn’t. Maybe the best way for games to be about people is simply to inject more real people into the game.

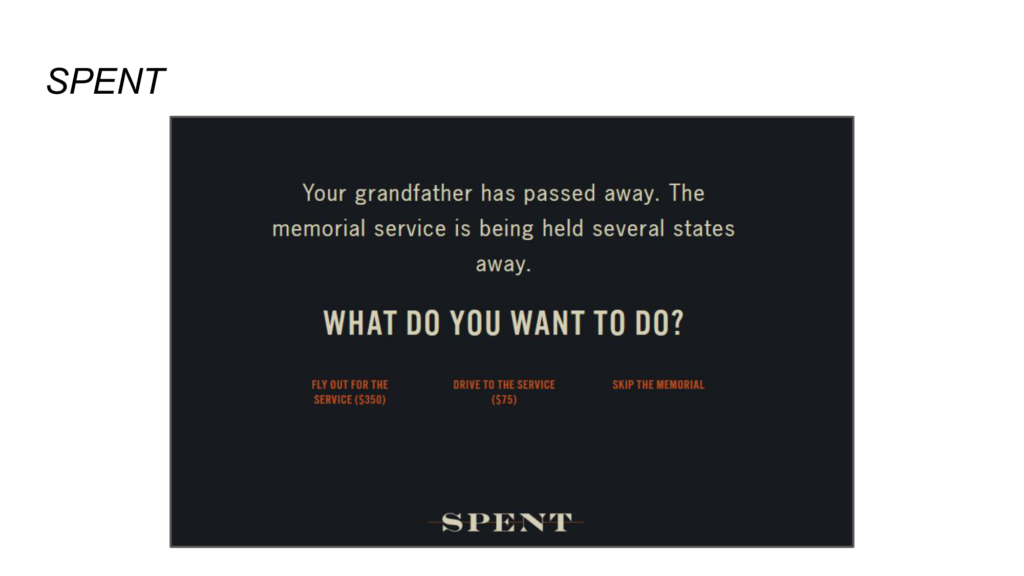

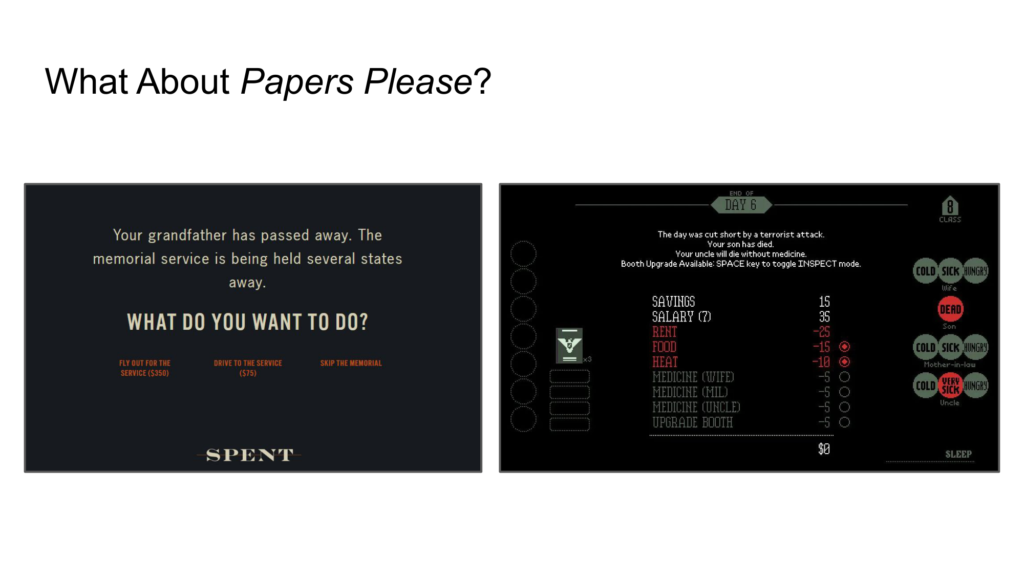

Let’s talk about another example of designer intent going awry. This is a SPENT, a well-intentioned game that wants to build empathy for the poor by showing players just how difficult their life can be, how they sometimes need to choose between paying the gas bill, repairing their car, and attending their grandfather’s funeral. That’s a bold goal, but is it effective?

One researcher aimed to find out. Here is an article from Psychology Today about an experiment she ran to see how effective SPENT was at increasing empathy for the poor.

She writes:

After I analyzed the results from this study, I was dismayed to find that playing the game had no effect on positive feelings toward the poor. In fact, the game had a negative effect on attitudes among certain participants – including some people who were sympathetic to the poor to begin with.

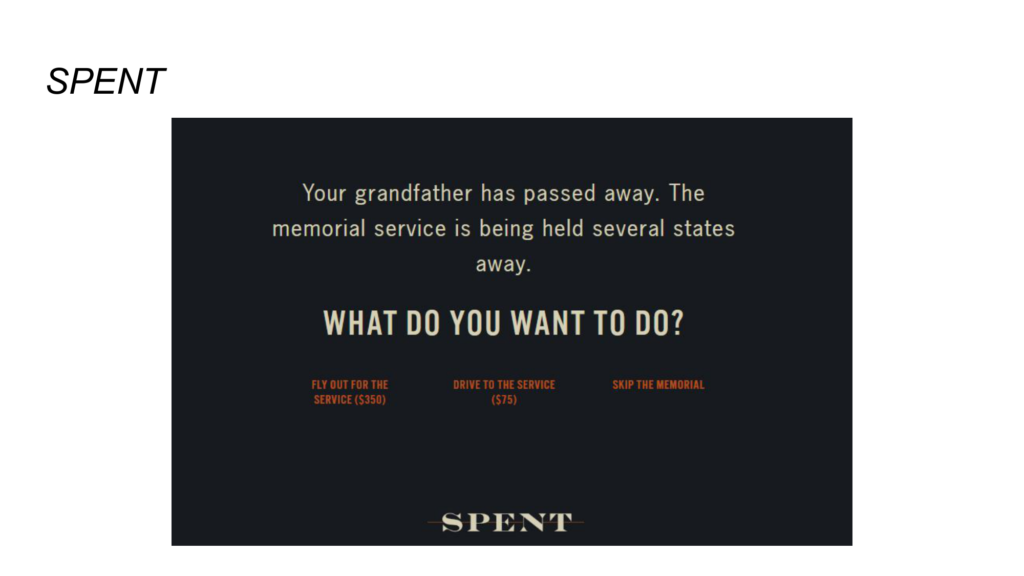

The problem is agency – when holding the mouse and making the decisions, it’s very natural to assume that the poor have the same agency that you do as the player. Consider this choice right here – should you spend the money to attend your grandfather’s funeral? The problem is that it’s very easy for the player to not spend the money by just hitting the Skip the Memorial button and then end up thinking: Why do these poor people have such a hard time saving their money?!?

One very interesting finding was that the game did produce empathy… when people watched the game instead of playing it. From my perspective, this is a devastating finding because the whole thing we as game designers have been going on and on about for decades is how games are empathy machines because they put you in the shoes of someone else’s life, but here we see the exact opposite effect, and to make it worse, a passive, non-interactive medium is the one that produces empathy instead.

However, maybe things are not so dire. Why, for example. does Papers Please succeed where Spent fails? The answer is actually just game design. Papers Please took the time and energy to give bite to your decisions – either from what happens when you turn away those in need or from how your acts of defiance hurt your family. In Spent, there is no actual cost to pressing the Skip the Memorial button and saving the money, which keeps the player from actually empathizing with the protagonist.

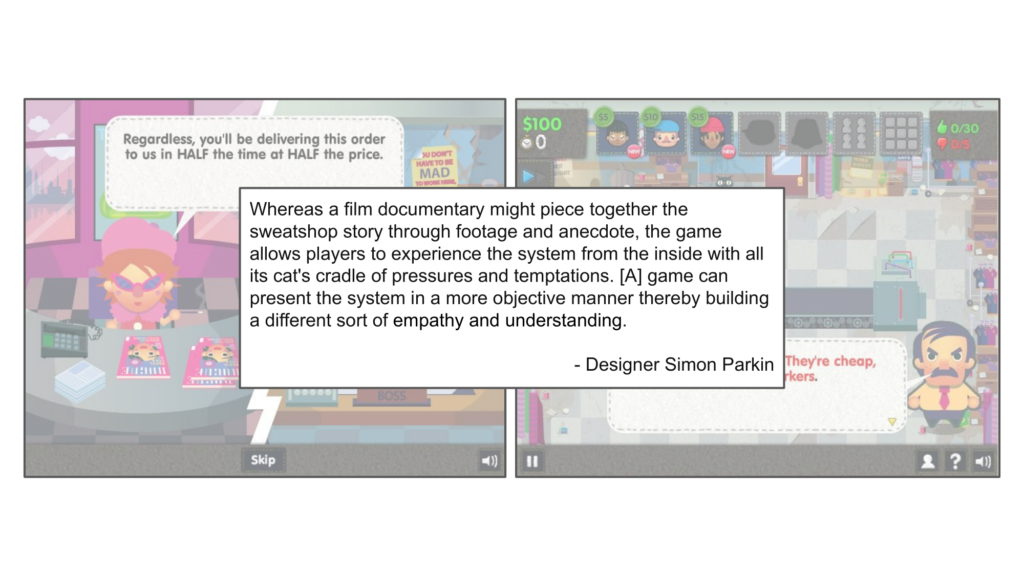

However, even if designers take the time to build out all of the mechanics needed to create real emotional tension, things can still go awry. Consider Sweatshop, a game designed to raise awareness about the hostile labor conditions in modern sweatshops. Indeed, this game earned the honor of being banned from the Apple App Store for its depiction of child labor and unsafe working conditions, which perhaps hit a little too close to home for them.

The game puts you in the role of the sweatshop manager who, in order to meet increasingly unreasonable quota demands from the corporation, has to cut corners by lowering safety standards, hiring children, and pushing workers past their limits.

This is what Simon Parkin, one of the designers, had this to say about their intentions and the game’s meaning:

Whereas a film documentary might piece together the sweatshop story through footage and anecdote, the game allows players to experience the system from the inside with all its cat’s cradle of pressures and temptations. [A] game can present the system in a more objective manner thereby building a different sort of empathy and understanding.

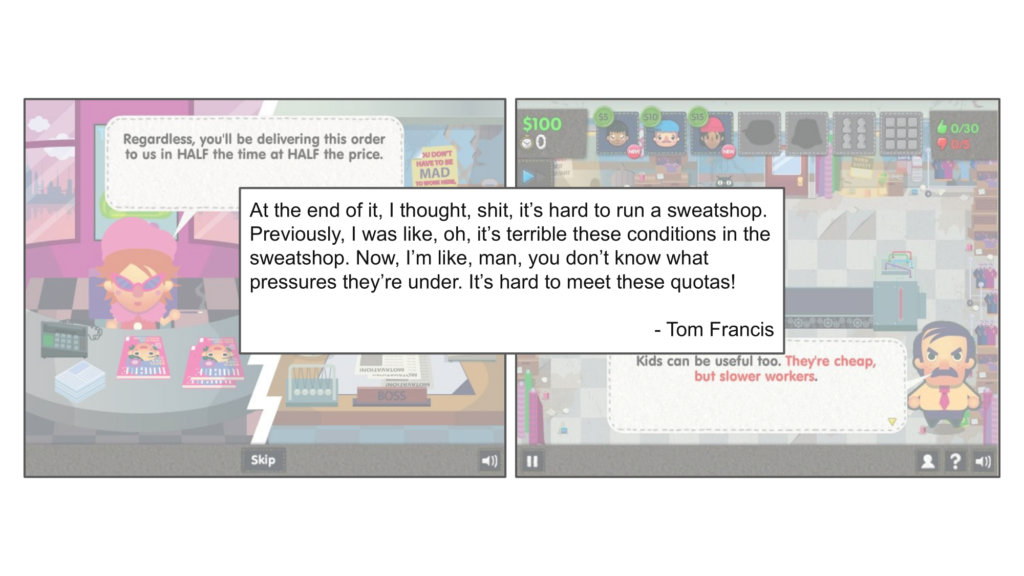

However, trying to get a message across with interactivity is playing with fire. This is what journalist and game designer Tom Francis said about his experience playing Sweatshop:

At the end of it, I thought, shit, it’s hard to run a sweatshop. Previously, I was like, oh, it’s terrible these conditions in the sweatshop. Now, I’m like, man, you don’t know what pressures they’re under. It’s hard to meet these quotas!

The problem is that the game puts you in the role of the manager, so your empathy is for the pressures he is under instead of the workers. You end up understanding why managers make the compromises they do and why children end up being mutilated.

Now, there are a couple of different ways to look at that. If players are able to step back and think about what they just did, it’s sort of amazing that a game could get you to kill kids to hit your t-shirt quota.

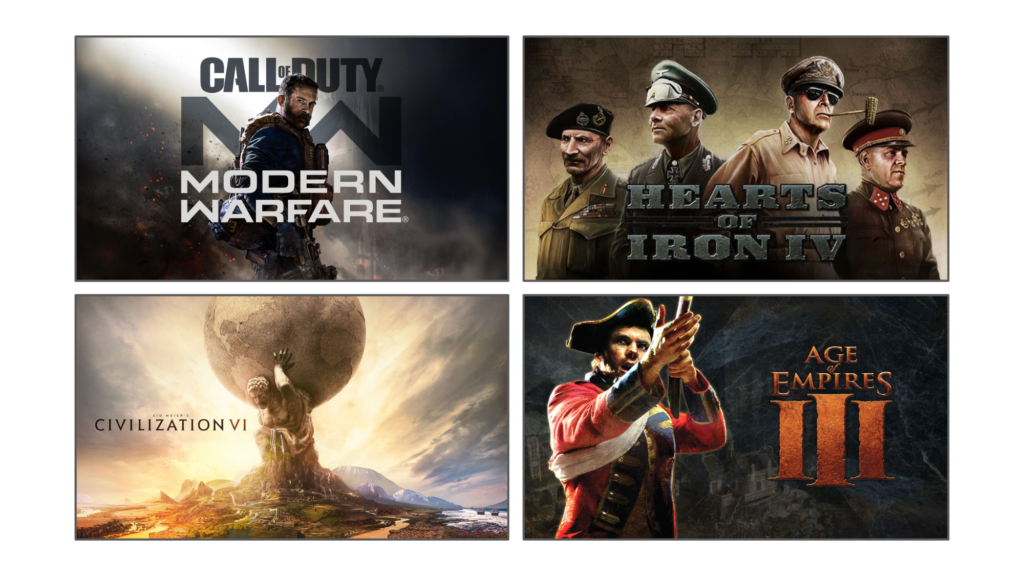

But I think it’s just as likely that, in less obviously baleful situations like a sweatshop, players will always subconsciously identify with whoever they control in a video game. What does that mean for games where you play the king, the queen, the ruler, or – more generally – the status quo, the existing power structure?

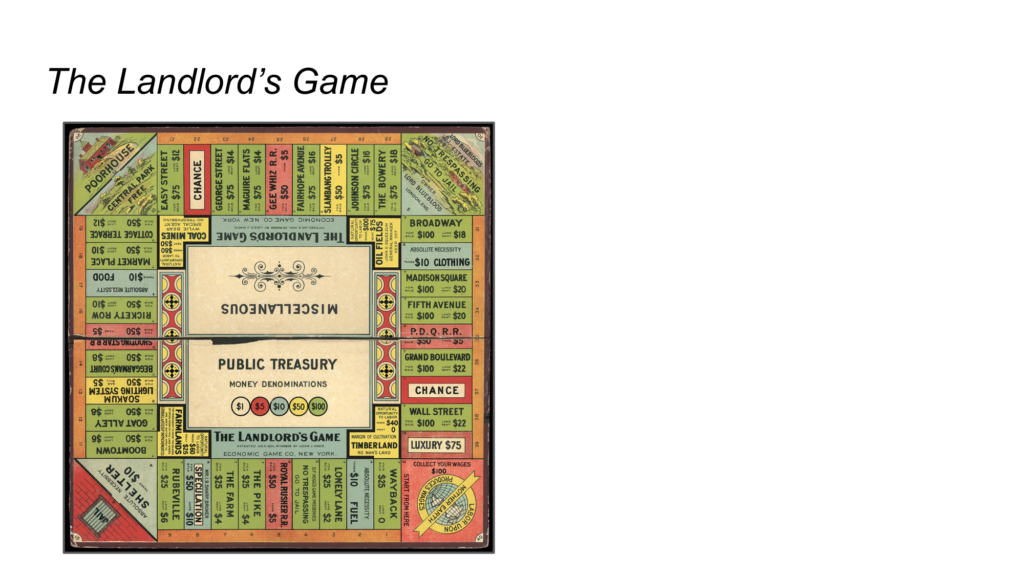

Perhaps the most famous example of a designer’s intent being thwarted is Elizabeth Magie’s The Landlord’s Game from 1906. It was designed to shows the negative effects of rampant capitalism, with an alternate set of rules to show how all the players would be better off if they adopted a tax system where rents were paid into the public treasury instead of into the landlords’ pockets.

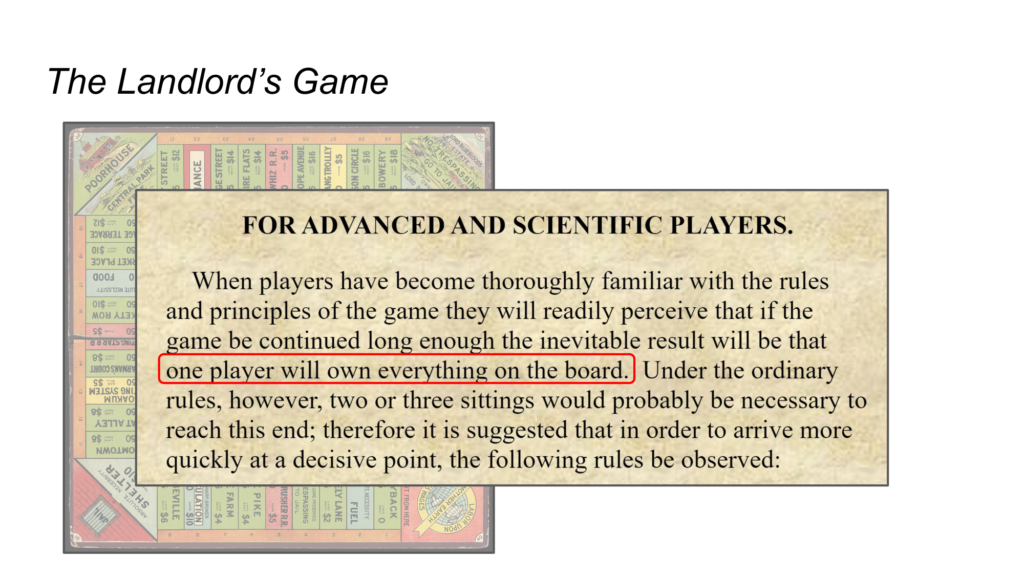

The original ruleset contain a very interesting passage that lays out the designer’s intentions. Magie points out that players will quickly realize that, under the default, monopolistic ruleset, “one player will own everything on the board.” The Landlord’s Game was Das Kapital made of cardboard and dice. She invented player elimination to prove out the evils of monopolies. Unfortunately for Magie, collecting rents from your properties and pushing your rivals into bankruptcy proved to be a lot more fun than having all the money going to the public treasury, and…

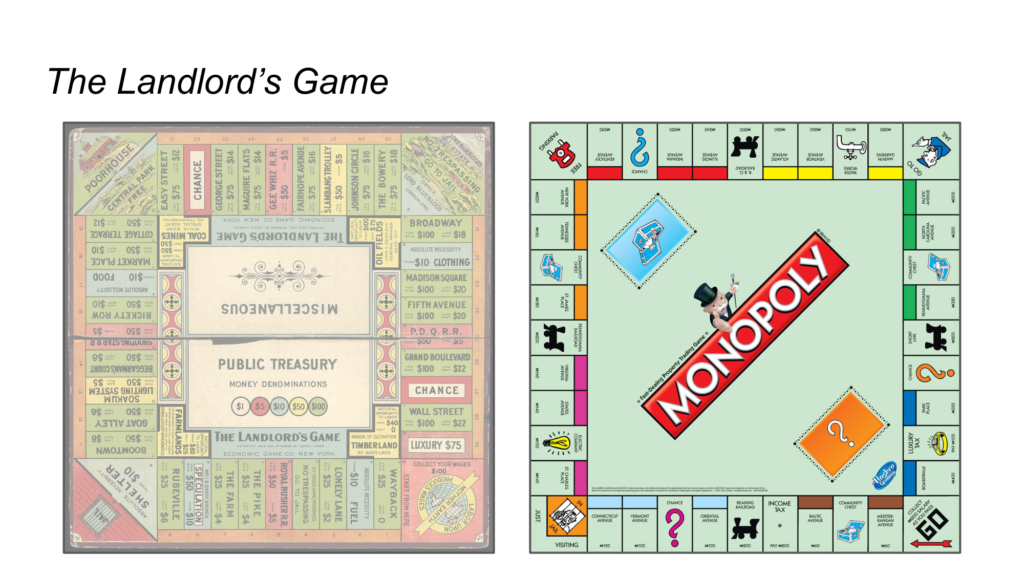

Today the game is known as Monopoly, minus the socialist tax ruleset. The lessons here are subtle – Monopoly absolutely does demonstrate how a capitalist system will concentrate wealth in the hands of the few and impoverish the many, which is what Magie intended after all, but I somehow doubt…

…this is exactly what she had in mind or if players perceive of the game as a critique of capitalism.

Fun is an insidious requirement for a game to be played and, perhaps more importantly, re-played. Games that aren’t much fun tend to just disappear, and we have to grapple with that as designers.

The very nature of a game makes it extremely difficult to express a strong position on an issue. In order to be a game with different potential strategies, Prison Architect has to suggest that rehabilitation and punishment are both equally viable options. The game-shaped box it is in prevents it from picking a side, regardless of what the designers think.

What it can do is show the problems with each path – you can punish prisoners by searching for contraband every day, which means your addicts will go into withdrawal when they can’t get their drugs and act out violently. On the other hand, you can create job training programs, but that lets the prisoners get their hands on screwdrivers and other items that can be turned into weapons. You can have visitation programs but then you’ll discover a pipeline of drugs being smuggled into the prison.

The game is not – and never could be – an accurate simulation of prison because that’s impossible, but it can help players understand the tradeoffs, compromises, and tensions that they may not have considered before playing.

Now let’s talk about Defcon, a game about nuclear holocaust. (We are really hitting the high points, aren’t we?)

An interesting study was conducted on how playing the game affected player’s opinions of nuclear war.

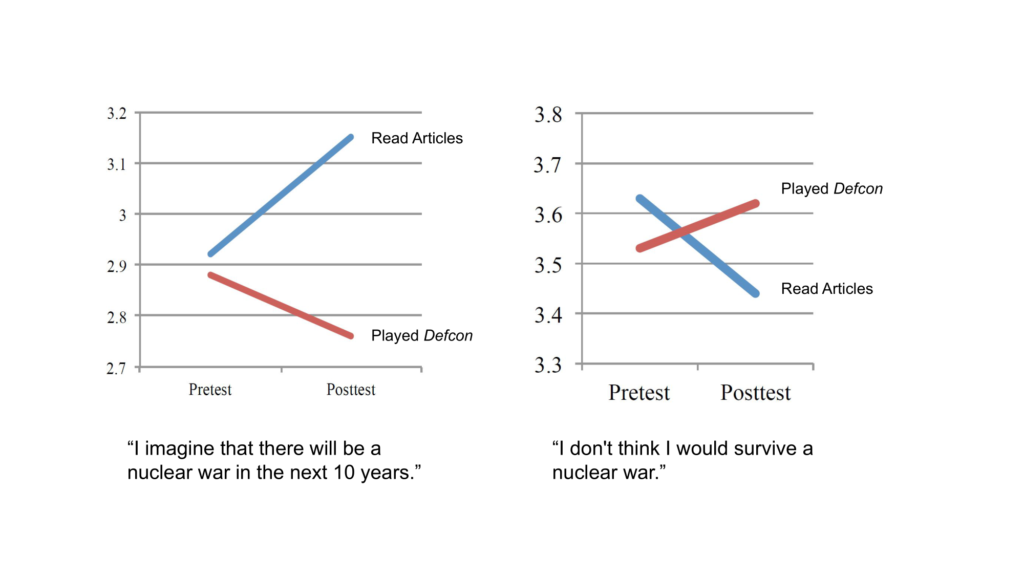

The experiment separated the subjects into two groups, a control group that read articles on the dangers of nuclear war and a treatment group which played Defcon instead. There were significant differences in how these two groups changed their opinion after the experiment. Although the control group became more worried about a nuclear war in the near future, the Defcon players strangely became less concerned. On the other hand, the game players were more pessimistic that they would survive a war. The researchers’ conclusion, based also on qualitative data, was that playing Defcon was more effective at showing players how destructive nuclear war would be so that they then assumed that our governments would be more incentivized to never resort to nuclear war.

However, there is one important wrinkle in the overall results, which are divided up here by high, medium, and low frequency gamers. Note that every single group became more concerned about the threat of nuclear warfare except for one – the high-frequency gamers in the treatment group, meaning the ones who play games the most frequently. The hypothesis is that core gamers quickly saw past the setting and no longer saw a game about nuclear war and instead saw an RTS game with an unusual art style. This highlights a huge challenge for trying to communicate using game design – if you are working within familiar genre constraints, over time, both the game’s setting and meaning will eventually disappear.

A similar finding showed up in a study run by Dr. Stephen Blessing and Elena Sakosky based on a Geoff Engelstein thought experiment about whether players of Incan Gold would change their behavior based on simply changing the setting of the game. Incan Gold is a push-your-luck game where you delve into an ancient temple for gems and artifacts but risk losing it all the farther you go. To see if the setting affected players, they reskinned the game twice – first, as a firefighter game where you rescued victims instead and, second, as an abstract version where you are just playing for points.

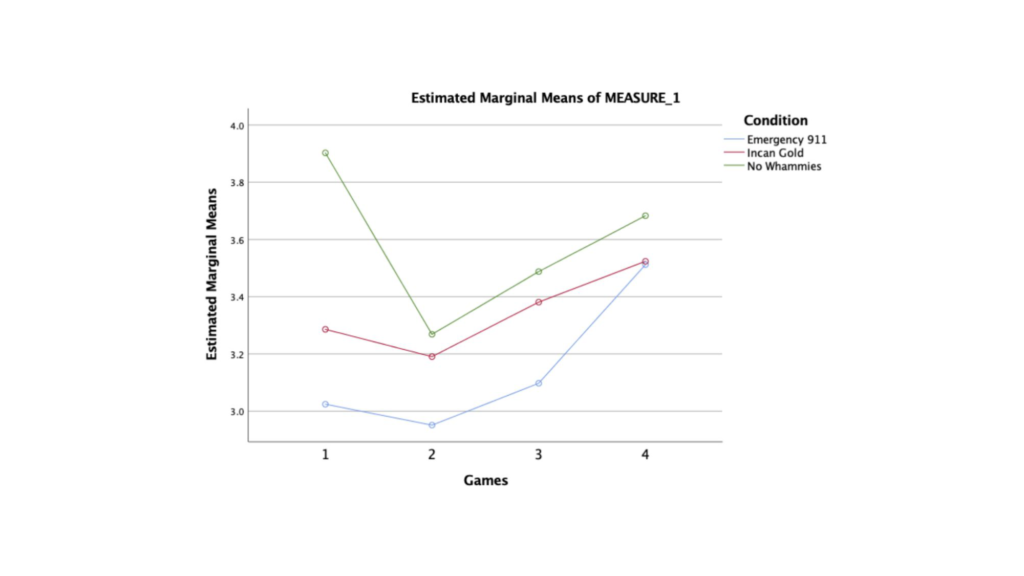

The results they found were that players did change their behavior based on the setting, at least at first. This graph shows how often players returned to the base, which means that they have stopped pressing their luck. In the firefighter setting, this means rescuing less victims, while in the abstract version, it simply means scoring less points. In the experiment, the firefighters would push their luck more, taking more risks to save more people. However, and this is the important part, by the fourth game, the results had largely converged and players of all three versions were playing the same way. Players were now seeing past the setting and just optimizing to score the most points, whether they were called gems or victims or just points. Setting can matter, but we need to be aware that players will eventually gravitate to the game’s inner logic and start to ignore the setting. The more the setting and the rules are disconnected, the bigger a problem this becomes.

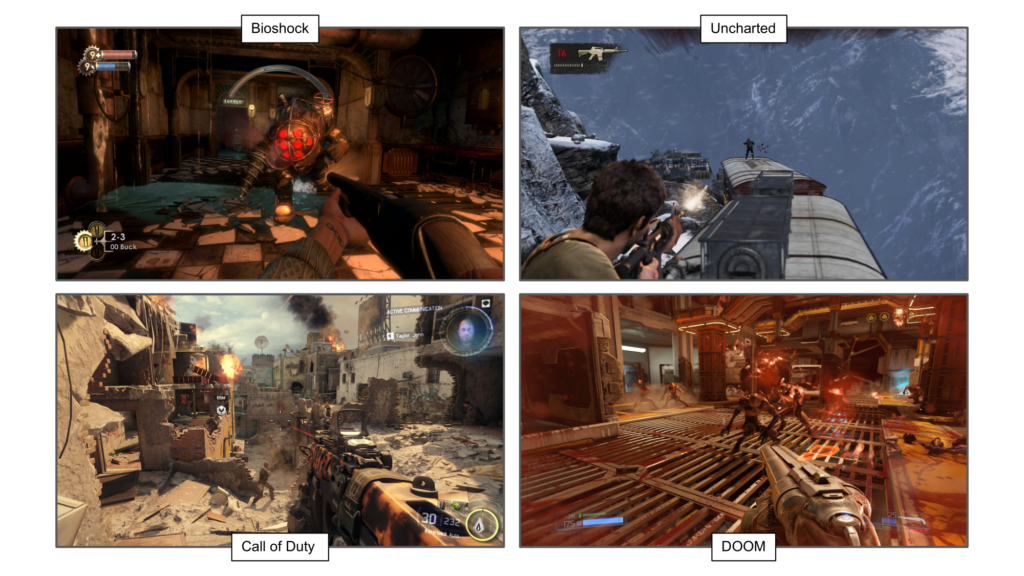

These four games have very different settings and meanings, with a very different set of messages and emotions for the player. And yet, there are significant parts of these four game that play out the exact same way, could even be built on the same shared codebase. Putting players into an established genre dulls the designer’s intent because, over time, players will stop engaging with the message and meaning of the game and instead just fall back on instinct. They are now playing shooter #34, not a philosophical game about a submerged dystopia or a jaunty adventure with a lovable rogue or a contemporary high-tech military thriller. Instead, players are warped back into their dorm room in 1994 and booting up Doom. Meaning is not a layer built on top of someone else’s game. A game’s meaning starts with its basic building blocks, the core actions that the player is going to be repeating over and over again.

Pingback: You Have No Idea How Hard It Is To Run A Sweatshop, Part 1 | DESIGNER NOTES

Pingback: You Have No Idea How Hard It Is To Run A Sweatshop, Part 3 | DESIGNER NOTES