The following was published in the March 2009 issue of Game Developer magazine…

One of the first things that separated video games from board, card, and parlor games was real-time interaction. The computer could handle all the details and challenges inherent in allowing two (or more) people to play the same game at the same time. Indeed, despite the name, the first multi-player video games may have had their roots more in sports than in games. Pong, after all, was inspired by table tennis. These early experiences were inherently synchronous, meaning that the players experienced the game together, at the same time, on the same machine. Since then, the synchronous format has been the default model for multi-player video games, and – with the arrival of online gaming – this same experience could be enjoyed even by people who were not necessarily in the same location.

The synchronous model is so deeply embedded in the standards and traditions of the industry – think Doom, StarCraft, Madden, EverQuest, and so on – that few designers consciously consider that synchronous play is simply a design choice. Another option exists – asynchronous play, meaning multi-player games that can be experienced in bite-sized chunks at different times for each player. The board-game world provides examples of games which can be played using this format, such as play-by-mail chess or wargames. The most successful game for this format is clearly Diplomacy, the classic game of back-stabbing, which rewards secret negotiations and hidden pacts difficult to achieve in a synchronous format. Indeed, with the appearance of the Web, a number of unofficial sites have sprung up giving players a moderated, asynchronous Diplomacy experience online.

One of the reasons Diplomacy works so well as an asynchronous game is that the turns are executed simultaneously. In other words, unlike sequential games like chess, in which players take turns performing actions, all moves in Diplomacy are done at the same time. Players submit their orders secretly to a gamemaster who then handles all interactions and conflicts according to the carefully crafted rules. This format is ideal for an asynchronous experience because all players get to make a decision every single turn. More traditional board games, from Risk and Monopoly to Carcassonne and Ticket to Ride, would slow down to a painful crawl in asynchronous play because the vast majority of turns are spent waiting for other players to make their moves. Thus, asynchronous play favors a specific style of game mechanics, ones which minimize waiting and keep players involved as much as possible.

Games for Real People

Asynchronous games hold a number of advantages over their synchronous counterparts. To begin, the time pressure of a standard turn-based game is eliminated. No more are 4 or 5 other gamers sitting around a table, waiting for the slow player to make up his mind. Instead, a player could take an hour deciding what to do without negatively impacting the flow of the game. Furthermore, asynchronous play allows multi-player gaming – still the richest, most engaging experience available – to fit the schedule of regular people with busy lives and unpredictable free time, across multiple time zones. Few adults can afford the total devotion required to participate in a five-hour, 40-man MMO raid. In contrast, an asynchronous game can allow a large group of friends to play together as long as each player can find 15 minutes per day to check the game. In Diplomacy, the English player can submit her moves in the morning, and the French can do it at night – or vice-versa – whatever works best for each one.

Indeed, the ideal online asynchronous game goes a step further than Diplomacy, which can still hang if one player neglects to send in a turn, by moving to a real-time format in which the game progresses regardless of an individual player’s specific actions. In fact, fantasy sports games follow exactly this model. Once a league is initiated, scores are tabulated each day of the season whether players log-on or not. However, the players are all full participants in their league whether they check their teams once every other week or hit the waiver wire multiple times per day. The strength of this model can clearly be seen by the astounding popularity of online fantasy leagues, with at least 30 million North American players in 2007, according to a study by the Fantasy Sports Trade Association. (In fact, a case could be made that fantasy sports are the most popular form of multi-player gaming in the world.) Players with different commitment levels can play together and still enjoy the experience – a statement which definitely cannot be made about your typical RTS.

Looking to the Web

Few good examples of asynchronous gaming exist for AAA retail video games, besides some play-by-email modes for older strategy games. For Civilization 4, we created a PitBoss (“Persistent Turn-Based Server”) option which allowed large games of up to 32 players in which players could log-on at any time to execute their turns. Combined with simultaneous movement and a 24-hour turn timer, epic games of Civilization were finally manageable thanks to the asynchronous format. One could also say that World of Warcraft‘s focus on solo content is a form of asynchronous play, in that players could finally participate in a traditional MMO without needing to juggle the logistics of managing a raid schedule or looking for a pick-up group. Furthermore, Leaderboards and Achievements are also a form of asynchronous interaction layered on top of traditional single-player or synchronous multi-player games, enabling a extra level of socialization for gamers across multiple sessions.

However, most of the innovative asynchronous games exist on the Web, a platform already built upon asynchronous interactions. Many Facebook games, like Wordscraper (née Scrabulous), manage the persistence of simple turn-based games while using the social networking aspects of Facebook to make it easier to challenge one’s friends. Games can be played between two friends over a few hours or a few months – whatever matches their level of commitment. Asynchronous MMOs exist as well, such as Mob Wars and Knighthood on Facebook or Nile Online and Travian on their own sites.

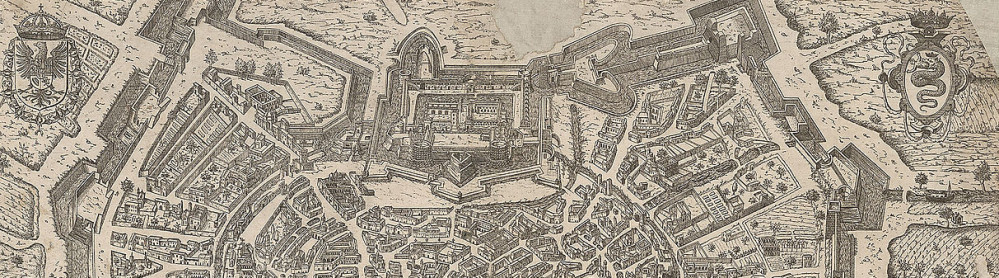

All of these games allow players to grow and develop some entity within a larger world, for prestige or challenge or the simple pleasures of levellings. In Nile Online, for example, players control a city on the banks of the Nile, each one with a unique resource, such as cedar, gold, or oil. As the cities grow, they begin trading with nearby players to acquire the resources they need – perhaps bronze for sculptures or emeralds for jewelry – or to sell their own excess goods for a profit. Eventually, players can see their cities rise in the global rankings or create great Monuments for further renown.

Meaningful Interaction?

The challenge with these asynchronous MMOs is that, while they do have some of the advantages of a multi-player environment, they tend to feel more like a less predictable single-player game. Player interaction is fairly light as most of mechanics focus simply on developing one’s own domain, without much concern for the neighbors. Allowing meaningful interaction between players is a challenge because, by definition, the system can only assume one player is logged-on at a time. If one player could wipe out another player’s city, what if the latter player is asleep? Would it be fun to wake up and discover all of one’s hard-earned progress destroyed without a chance to counter the attack?

Thus, most of the games include options to lessen the impact of other players’ actions. In Travian, for example, a player can build a Cranny which automatically protect her resources when another player ransacks the town. However, these mechanics are ultimately self-defeating; player interaction is either meaningful or it is not. If zero-sum mechanics, like resource raids, are too powerful and negate the advantages of asynchronous play – the ability to set one’s own play schedule – then the developers should focus on the parallel competition mechanics of the game instead, building a Wonder first or achieving economic dominance.

One asynchronous web-based game which tries to solves this problem while keeping meaningful zero-sum mechanics is Duels, a fantasy-themed MMO in which characters level up by fighting one another. The system is asynchronous because players do not actually need to be online when their characters fight. Instead, a warrior might challenge a wizard to a duel, which is only played out when the wizard actually accepts the challenge later that same day. The advantage is that while the conflict and interaction is meaningful, the players themselves can still play the game at whatever pace they prefer without worrying about looking for games in the lobby or rage-quitters spoiling the battles. However, the problem is that, because players can be offline when combat occurs, no meaningful decisions actually occur during the duel itself. Thus, combat is a “black box” which takes in two characters and spits out a result. If a good game should be a series of interesting decisions, Duels paints itself into a corner by taking control away from the player.

Native Asynchronous Play

Truth to be told, asynchronous games are still in their infancy from a design perspective. Their future is promising as the potential audience for asynchronous multi-player games is much great than the potential audience for synchronous ones – although anyone who can find time for synchronous games can find time for asynchronous ones, the opposite is not true. The challenge is, instead of aping mechanics from established synchronous games, finding game mechanics native to the format itself, ones which make sense only in an asynchronous world. The best example of such a game is Parking Wars, a Facebook game in which players earn money by parking for an extended period of time on another player’s street. The trick is that if a car is parked illegally, then the owner of that street can steal all the money the car had earned by handing out a parking ticket.

Thus, the best strategy is knowing what times one’s friends are less likely to be checking their streets for illegally parked cars and using that knowledge to earn money. The counter-strategy, of course, is to check one’s own street at unexpected times to catch one’s friends trying to do the same. Thus, the game cleverly uses the actual time players are off-line as the game’s content. Unlike the mechanics of the other asynchronous games mentioned previously, the rules behind Parking Wars could not work at all in a synchronous environment. Designers of future asynchronous games should follow this precedent – the time has come to stop retrofitting synchronous mechanics into an asynchronous shell and to find the format’s native voice.