The following was published in the March 2010 issue of Game Developer magazine…

As examined in Part I, a game’s meaning springs from its mechanics and not necessarily from its theme, especially if the two are in conflict. Such a dissonance can leave players feeling lost, perhaps even cheated. Thus, designers should strive to keep the two in harmony. At the very least, they should not be fighting each other.

When they do, the game’s mechanics can actually undermine the theme that the designers want to deliver. For example, Bioshock presents players with a true ethical choice – “harvest” Little Sisters by destroying them or “rescue” them by releasing their minds? The reward for harvesting is double Adam (the game’s genetic-modification currency), which tempts players to choose a morally disturbing path.

However, the game sprinkles other rewards on players who rescue Little Sisters, so that the ultimate difference between the two paths is negligible from a statistical perspective. Players are told by the game’s fiction that their choice matters – that they are making a sacrifice by deciding to rescue the little girls – but the game’s mechanics tell them a different story. Of course, when theme and mechanics are in conflict, players know which one actually matters, which one is actually telling them what the game is about.

Similarly, many traditional RPG’s put the player in an odd position. By giving the player an epic goal from the beginning (“Kill the evil wizard!”), the game casts him in the role of the world‘s savior. However, the actual gameplay involves roaming the countryside killing most of what falls in the player’s path and looting everything else. The story tells the player that he is a hero, but the game rewards him for being something else. Richard Garriot directly attacked this dissonance when he designed Ultima IV, by making the game about achieving eight virtues instead of simply killing his way to a “Foozle” at the end.

A Perfect Union

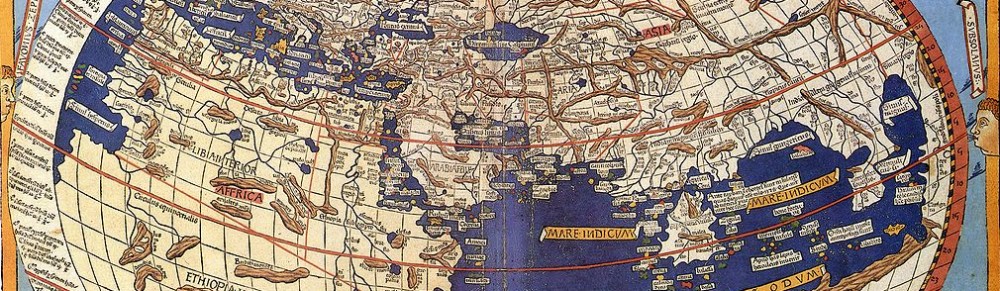

Sometimes, a designer does achieve a perfect union of theme and mechanics. One example is Dan Bunten’s Seven Cities of Gold, the classic game of exploration. Bunten lost his way one day while hiking in the Ozarks and imagined a game in which the player struggles to keep her bearings in an unfamiliar landscape. From that seed, Bunten took the next step and chose a perfect theme – the age of the conquistadors, of Columbus, Cortez, and Pizarro, who were always partially lost – which provided wonderful raw background material with which to work.

Certain categories match theme and gameplay particularly well, including Wii games (Wii Sports), music games (Rock Band), tycoon games (Railroad Tycoon), sports games (Madden), flight sims (Wings), and racing games (Gran Turismo). Notice that while these examples are based on real-world activities, which helps to keep the mechanics tied to the theme, a designer does not need to put verisimilitude above all else.

In fact, one could argue that Mario Kart is more truly about racing than Gran Turismo is – the former’s rapid exchange of player position as shells fly around the track is perhaps closer to many players’ ideal concept of racing than a stodgy simulation’s more fixed positioning. Put another way, which object is more about Guernica – a photograph of the city’s ruins or Picasso’s masterpiece of anguish?

Further, great games can emerge when the theme simply provides an excuse to experiment with certain mechanics. Left4Dead is not really a game about zombies, after all – it’s a game about teamwork. The designers created each special zombies to encourage players to work together as a team – the hunter punishes loners, the tank requires concentrated fire, the witch demands close communication, and so on. The zombie theme simply gave the designers a plausible backdrop in which they could experiment with game mechanics that encouraged teamwork over solo play.

Does Civilization Fail?

The Civilization series provides an interesting study in the challenges inherent in trying to match theme with meaning. The games are purportedly about the sweep of world history, but one does not have to play long before cracks start to show.

To begin, societal progress is constant throughout the game – the player’s civilization can never fall into a dark age or split apart in a civil war. The user community has dubbed this dynamic the “Eternal China Syndrome.” The only entropy a player experiences comes from external invasion.

Indeed, the game actually provides a “Start a Revolution” button, so that the player can change government but only when convenient. (I’m sure Louis XVI would have appreciated such a system!) Indeed, all actions in the game are conducted top-down – the player is some strange combination of king, general, tycoon, and god.

The source of these conflicts with real history is the problem of player agency. In order to be fun, the player needs to be in control. Moreover, the consequence of each decision needs to be fair and clear, so that players can make informed choices, plan ahead, and understand their mistakes. Real history, of course, is much messier and difficult to understand, let alone control.

In fact, the game’s mechanics tell us less about world history than they do about what it would be like to be part of a league of ancient gods, who pit their subjects against each other for fun. These immortal opponents, after all, are the only characters that can destroy the player. The people themselves have little say in how history will develop.

However, player agency is actually a good thing; indeed, it is at the very center of what makes games so powerful. Perhaps some topics are simply too broad or vague or slippery to be addressed by a game’s mechanics, and – sometimes – themes can just be themes, with the player knowingly entering a fantasy space that speaks not directly to the topic but to some other need or desire.

In the case of Civilization, the desire is to control history, which may not teach us much about it, but it is not without value. Indeed, the game fares well when compared with other artistic disciplines. Few works of art tackle the sweep of world history, and the ones that exist (Birth of a Nation) are often dangerous works of ideology.

Designers who care to make games that actually speak to us about history should focus on a specific era or event, such as Bunten’s Seven Cities of Gold or Meier’s Railroad Tycoon. Put the player in the shoes of a flesh-and-blood person – let her explore the challenges and opportunities of the times but within mortal limits.

Why Theme Matters

Although a game’s theme and mechanics can tell different stories, society at large does not understand that there is a difference between the two, and if the theme is appalling to the mainstream, a good game can be unfairly tarred. For example, Grand Theft Auto has a theme of crime and urban chaos, but the game is actually about freedom and consequence. Every crime increases the player’s notoriety, which can end the game if the police send enough firepower.

Nonetheless, to the mainstream, GTA was simply about killing hookers and running over pedestrians – for outsiders, the game couldn’t be “about” anything else. Players, however, understood that the game was giving them something different – an open-world in which their decisions actually mattered. Consequence was the true killer feature.

Crackdown provides an interesting contrast in that it delivers the same open-world simulation with consequence as GTA but with a theme (fighting crime as a super-cop) much more palatable to the average person. Rockstar may have record sales to show for their work, but designers who believe they have a responsibility to society at large should take note that the criminal theme was not inevitable.

Today, many designers strive to achieve two worthy goals – reaching a mass audience and creating great art. However, both are at risk if theme and mechanics are in dissonance. The average consumer, who is not highly literate in the standard tropes of game design, expects video games to be about whatever is on the cover. Pulling a bait-and-switch – or simply not thinking critically about the lessons that a game actually teaches – will only turn new players away.

As for the question of art, one must first recognize that many great works of art are abstract. Lyrics may give some meaning to a song, but a symphony is generally meant to be interpreted and enjoyed however the listener prefers. Similarly, games can stand on their own without specific themes – Tetris being the obvious example.

Furthermore, even a pasted-on theme can work if the designers are not promising more than the game can deliver – San Juan and Race for the Galaxy are both brilliant, yet similar, card-based adaptations of Puerto Rico. That one is set in the Caribbean and the other in outer space is not a problem as the games are clearly not marketed as re-creations or simulations. The theme simply adds flavor.

However, great art never has theme and meaning in open conflict, in the way many games do. Othello is actually about the “green-eyed monster” of jealousy and not just the life of a Moor in the 16th-century Venetian military, but the latter does not detract from the former. Can the same be said about Bioshock? About Spore? About Civilization? These games do claim to be about something – do their mechanics tell the same story? To touch people, the play itself needs to deliver on the theme’s promise.