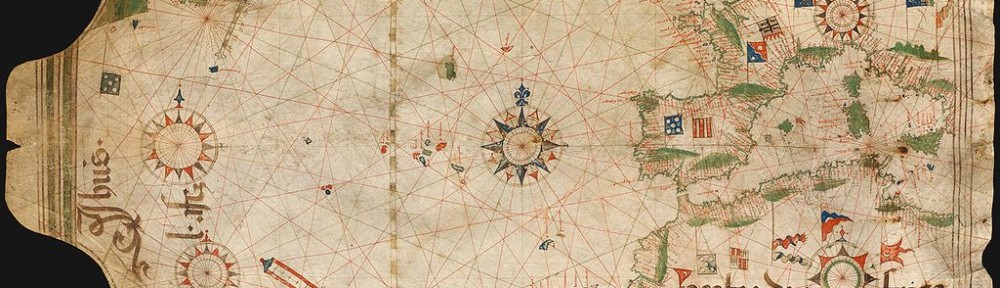

Valve recently released some very interesting stats, including Death Maps, from HL2: Episode 2 and Team Fortress 2. What are Death Maps? Well, here’s one from the Gravel Pit map for TF2:

I can attest to dying (and killing) quite a few times near the C node in the lower-left corner. Looks like I’m not the only one.

As a designer, I find the TF2 stats fascinating – I would have loved to see similar info on how people played Civ4. Obviously, some of the results are unsurprising. Scouts get the most captures by a ratio of 2:1 over the next best class, the Pyro. Snipers get the most kills. Medics get the most assists. The points category has a little more balance as it includes a number of factors, but there is still a big spread between the Sniper’s 67 points/hour to the Engineer’s 41. The big question, of course, is what Valve should do with this info when balancing the game.

The idea of game balance is a tricky one because many people assume that, in a well-balanced game, all options should be equally valid. Rock, Paper, Scissor is the classic example of an “equally balanced” game, and bringing it up allows me to reference Sirlin’s excellent article on why RPS is a terrible game:

A simple rock, paper, scissors (RPS) system of direct counters is a perfectly solid and legitimate basis for a strategy game provided that the rock, paper, and scissors offer unequal risk/rewards.

Consider a strictly equal game of RPS. We’ll play 10 rounds of the game, with a $1 bet on each round. Which move should you choose? It makes absolutely no difference whether you choose rock, paper, or scissors. You’ll be playing a pure guess. Since your move will be a pure guess, I can’t incorporate your expected move into my strategy, partly because I have no basis to expect you to play one move or another, and partly because I really can’t have any strategy to begin with.

Now consider the same game of RPS with unequal payoffs. If you win with rock, you win $10. If you win with scissors, you win $3. If you win with paper, you win $1. Which move do you play? You clearly want to play rock, since it has the highest payoff. I know you want to play rock. You know I know you know, and so on. Playing rock is such an obvious thing to do, you must realize I’ll counter it ever time. But I can’t counter it (with paper) EVERY time, since then you could play scissors at will for a free $3. In fact, playing scissors is pretty darn sneaky. It counters paper—the weakest move. Why would you expect me to do the weakest move? Are you expecting me to play paper just to counter your powerful rock? Why wouldn’t I just play rock myself and risk the tie? You’re expecting me to be sneaky by playing paper, and you’re being doubly sneaky by countering with scissors. What you don’t realize is that I was triply sneaky and I played the original obvious move of rock to beat you.

In other words, there is no such thing as an “equally balanced” game which is still fun and not just random. Instead, fun games tend to have a “free market” of balance, which ebbs and flows based on the desirability of certain decisions. Scouts and engineers are always going to be important because they are, respectively, the purest offensive and defensive classes. Indeed, these two classes are also the two most popular. However, the Spy can use the sapper to destroy an Engineer’s turret pretty easily, and Pyros are good at lighting Scouts on fire. The Heavy gets the most kills but – as a slow mover – is vulnerable to the Sniper, who is in turn is vulnerable to the Demoman’s grenades. And so on.

The key is that the circle is not complete. Many of the counter units – the Demo, the Pyro, the Spy – do not have counters themselves because there is less incentive to play them in a vacuum. In Sirlin’s words, the classes offer “unequal risk/rewards.” If you play an Engineer, and no one on the other side is playing a Spy, your team is going to have great defense. On the other hand, as more and more people pick Engineers, the more attractive the Spy will become. Nonetheless, the most important goal is to have good defense, not to just be able to screw with the Engineers.

So, we are back at the question of what Valve should do with the stats. By definition, the counter units should never be more popular than the classes they are countering. Thus, it’s ok that the Engineer is twice as popular as the Spy. On the other hand, Valve should certainly learn something from these stats… but exactly what is a bit of a mystery.